The Deadly Hue: The Poisonous History of Bright Green Colors

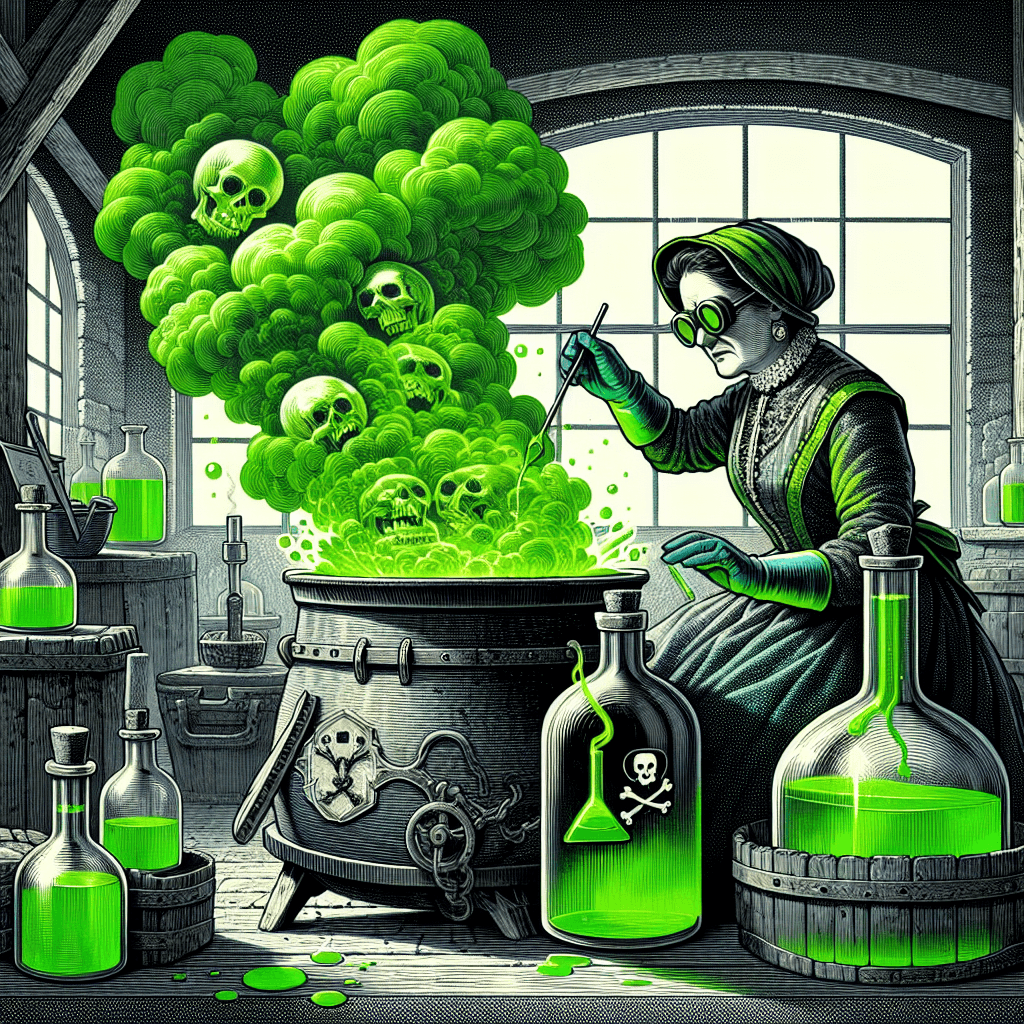

In the 18th and 19th centuries, achieving a stunning emerald green in fashion and decor came at a terrifying cost. These captivating colors harbored a deadly secret: they were created using arsenic.

Too Long; Didn't Read

Historically, vibrant and sought-after green colors were made with arsenic, a highly toxic poison, making beautiful clothing and wallpaper deadly.

The Deadly Hue: Why Did Creating Bright Green Colors Historically Involve Using Poison?

Imagine a stunning emerald green gown shimmering under gaslight or a room adorned with vibrant, leafy wallpaper. In the 18th and 19th centuries, achieving such captivating greens often came at a terrifying cost. While beautiful, these colors frequently harbored a deadly secret: poison. The intense, sought-after greens that defined fashion and decor during this era were largely created using arsenic, a highly toxic substance. This blog post delves into the fascinating and frightening history of why creating bright green colors historically involved using poison, exploring the chemistry, the allure, and the lethal consequences of these pigments.

The Challenge of Green

Before the late 18th century, achieving stable, bright green pigments was notoriously difficult. Traditional methods relied on:

- Vegetable Dyes: Often faded quickly or produced dull, yellowish-green tones.

- Mineral Pigments: Like verdigris (copper acetate), which was unstable, corrosive, and could darken or change color over time.

- Mixing Blue and Yellow: While seemingly simple, achieving a consistent, vibrant green through mixing was challenging, and the results often lacked intensity or longevity.

There was a clear demand, particularly driven by fashion and interior design trends, for a more brilliant, durable, and affordable green.

Arsenic Enters the Palette: Scheele's Green & Paris Green

The breakthrough, albeit a dangerous one, came with the advent of arsenic-based pigments.

Scheele's Green

In 1775, the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele developed a pigment by reacting copper sulfate with arsenic trioxide. The result, copper arsenite, became known as Scheele's Green.

- Why Arsenic? The arsenic compound yielded a bright, vivid green unlike anything easily achievable before. It was relatively inexpensive to produce and offered good opacity.

- Applications: It quickly found use in paints, wallpaper, fabrics, artificial flowers, candles, and even children's toys.

Paris Green (Emerald Green)

Around 1814, an even more vibrant and durable pigment, copper acetoarsenite, was commercially produced, often called Paris Green or Emerald Green.

- Enhanced Properties: It offered a richer, more intense emerald hue than Scheele's Green and proved more stable.

- Widespread Use: Paris Green became hugely popular, used extensively in fashion, home furnishings, paints, and, alarmingly, even as an insecticide and rodenticide (a clue to its toxicity!).

The key reason these arsenic compounds were used was simple: they delivered the specific, brilliant, and relatively stable green hues that artists, manufacturers, and consumers craved, at a viable cost.

The Poisonous Consequences

The beauty of these arsenic greens masked their lethal nature. Arsenic is a potent poison, and exposure to these pigments occurred in numerous ways:

- Manufacturing: Workers in factories producing the pigments or using them to dye fabrics and print wallpapers suffered heavily from inhaling arsenic dust and direct skin contact. Chronic exposure led to skin lesions, respiratory illnesses, organ damage, and death.

- Wearing Arsenic: Dyed clothing, especially ball gowns or accessories like artificial flower wreaths, could shed arsenic dust. Skin absorption through sweat or inhalation posed a constant risk to the wearer.

- Living with Arsenic: Arsenic-laced wallpapers were particularly hazardous. In damp conditions, molds could metabolize the arsenic compounds, releasing toxic arsine gas into the room. Numerous accounts exist of chronic illness and mysterious deaths later attributed to poisoned wallpaper – there's even speculation, though debated, that Napoleon Bonaparte's death in exile was hastened by arsenic from the green wallpaper in his residence.

- Accidental Ingestion: Pigments could flake off toys or contaminate food preparation surfaces.

Symptoms of arsenic poisoning ranged from nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea to severe skin sores, hair loss, convulsions, and eventual organ failure. The slow, cumulative nature of chronic arsenic poisoning often made it difficult to diagnose initially.

Fading Popularity and Safer Alternatives

Awareness of the dangers grew throughout the 19th century, fueled by medical reports, public health scares, and tragic incidents involving factory workers and consumers. While manufacturers initially resisted change due to the pigments' popularity and profitability, the mounting evidence became undeniable.

Gradually, safer synthetic green pigments, such as chrome greens and aniline dyes, were developed and began to replace their toxic predecessors. Legislation also played a role in curbing the use of arsenic greens in some countries. By the early 20th century, the deadly allure of Scheele's Green and Paris Green had largely faded from everyday life, though Paris Green continued to be used as a pesticide for some time.

Conclusion

The historical use of arsenic to create vibrant green colors serves as a stark reminder of the dangerous lengths humanity has gone to in the pursuit of beauty and innovation. Scheele's Green and Paris Green provided the brilliant hues demanded by 18th and 19th-century aesthetics, but their reliance on highly toxic arsenic exacted a heavy toll on health and life. Understanding this history underscores the importance of chemical safety and responsible innovation. While we now enjoy a vast spectrum of safe, synthetic colors, the story of arsenic green reminds us that beauty should never come at the cost of well-being.