Why did people in the 18th century wear massive powdered wigs

More than a mere status symbol, these towering hairdos were a surprisingly practical solution to rampant syphilis, persistent head lice, and the overwhelming stench of the 18th century.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: People wore them to hide baldness and sores from syphilis and to avoid head lice. They also became a massive status symbol; the bigger the wig, the richer you were. The scented powder helped cover up bad smells.

Beyond the Bouffant: Why Did People in the 18th Century Wear Massive Powdered Wigs?

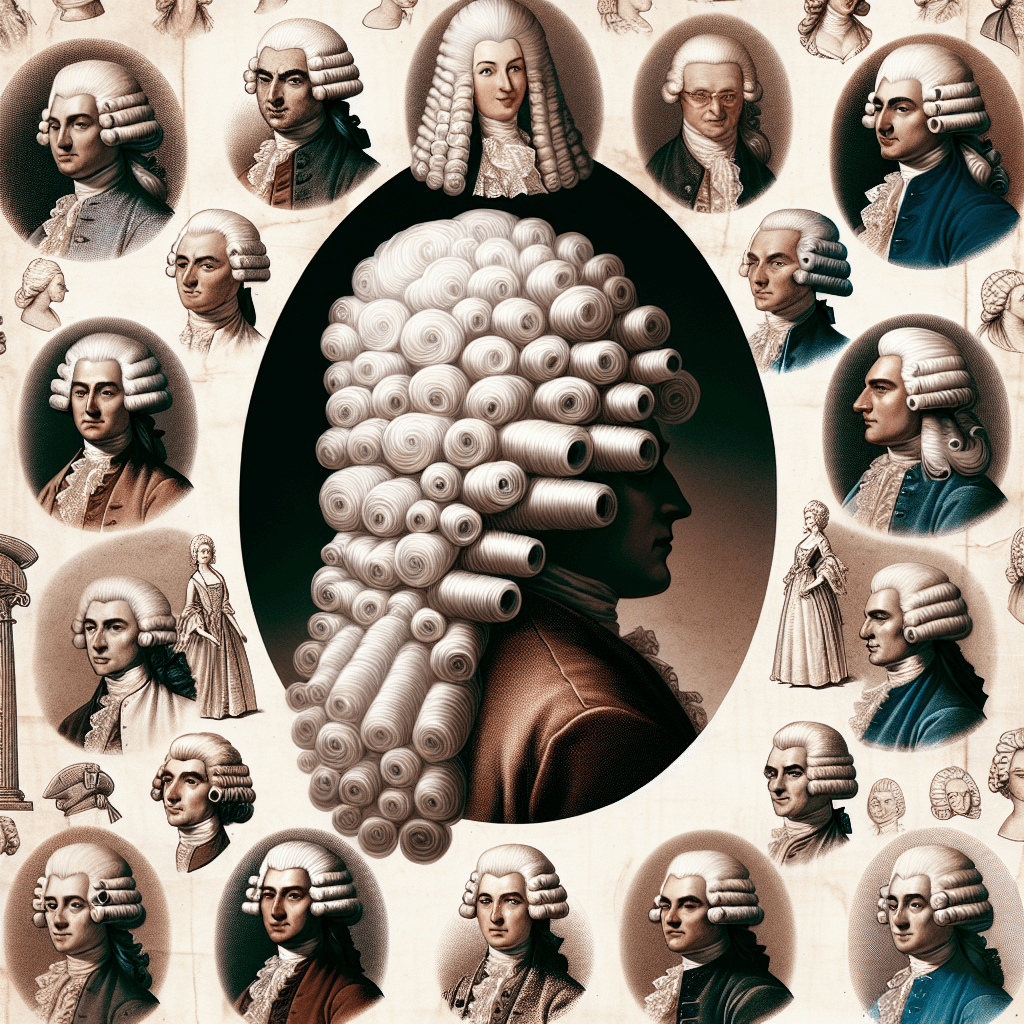

When you picture the 18th century, what comes to mind? For many, it's the striking image of towering, immaculately white wigs perched atop the heads of society's elite. From George Washington to Marie Antoinette, these elaborate coiffures, known as perukes, seem almost comically extravagant to the modern eye. But were they merely a bizarre fashion statement? The truth is far more practical and fascinating. These iconic wigs were not just about style; they were a direct response to a rampant disease, a solution for poor hygiene, and the ultimate symbol of a person’s wealth and status. This post will unravel the surprising and practical reasons behind one of history's most recognizable trends.

A Hairy Solution to Disease and Pests

Long before they became a fashion essential, wigs offered a pragmatic solution to some very unpleasant problems, primarily disease and lice.

The Syphilis Epidemic

Beginning in the late 15th century, a syphilis epidemic swept across Europe, leaving a trail of devastating symptoms. Sufferers often experienced open sores, painful rashes, and, most visibly, patchy and premature hair loss. In an era without antibiotics, a cure was impossible. To hide the embarrassing effects of the disease, many people began wearing wigs. The trend gained royal endorsement when King Louis XIII of France, who started balding in his early twenties, adopted a wig in the 1620s. His son, the famous "Sun King" Louis XIV, followed suit, cementing the wig as a respectable and fashionable accessory for European nobility.

The Louse Problem

Hygiene in the 18th century was not what it is today, and head lice were a common and persistent nuisance for people of all social classes. Treating them was difficult and unpleasant. The wig provided an ingenious workaround. A person could simply shave their head—or keep their hair cropped very short—and wear a peruke instead. This made personal hygiene far easier. More importantly, the wig itself, crawling with lice, could be sent off to a wigmaker for professional boiling and delousing, a much more effective process than trying to pick nits from one's own scalp.

The Ultimate Status Symbol

While wigs began as a practical tool, they quickly evolved into a powerful symbol of wealth, class, and influence. The term "bigwig," which we still use today to describe an important person, originated from this very trend. The bigger and more elaborate your wig, the more important you were.

- Costly Materials: The finest wigs were crafted from real human hair, which was expensive and highly sought after. Cheaper alternatives were made from the hair of horses, goats, or yaks.

- The Powder: The iconic white look came from powdering the wig with finely ground starch, often scented with pleasant aromas like lavender or orange blossom to mask other odors. This powder was a luxury item. In 1795, the British government even introduced a tax on wig powder, making it a clear and taxable indicator of wealth.

- Professional Uniform: Certain professions adopted specific styles of wigs to denote their authority and formality. This tradition famously survives in the British legal system, where judges and barristers still wear wigs in court as a symbol of their office.

The Decline of the Peruke

By the end of the 18th century, the era of the massive powdered wig was coming to a close. The French Revolution played a major role in its demise; the wig became inextricably linked with the aristocracy and the Ancien Régime, making it a politically dangerous accessory. Simultaneously, a new "natural" aesthetic began to take hold across Europe. The British wig powder tax of 1795 was the final nail in the coffin, making the style prohibitively expensive for all but the very wealthiest, and it quickly fell out of mainstream fashion.

Conclusion

The powdered wig of the 18th century was far more than a frivolous fashion choice. It was a clever response to widespread disease, a practical defense against pests, and a clear declaration of one's place in the social hierarchy. It solved real-world problems while simultaneously creating a distinct visual language of power and prestige. So, the next time you see a portrait of a stern-faced figure in a towering white wig, you'll know that their elaborate hairstyle tells a much deeper story about the medical, social, and political realities of their time.