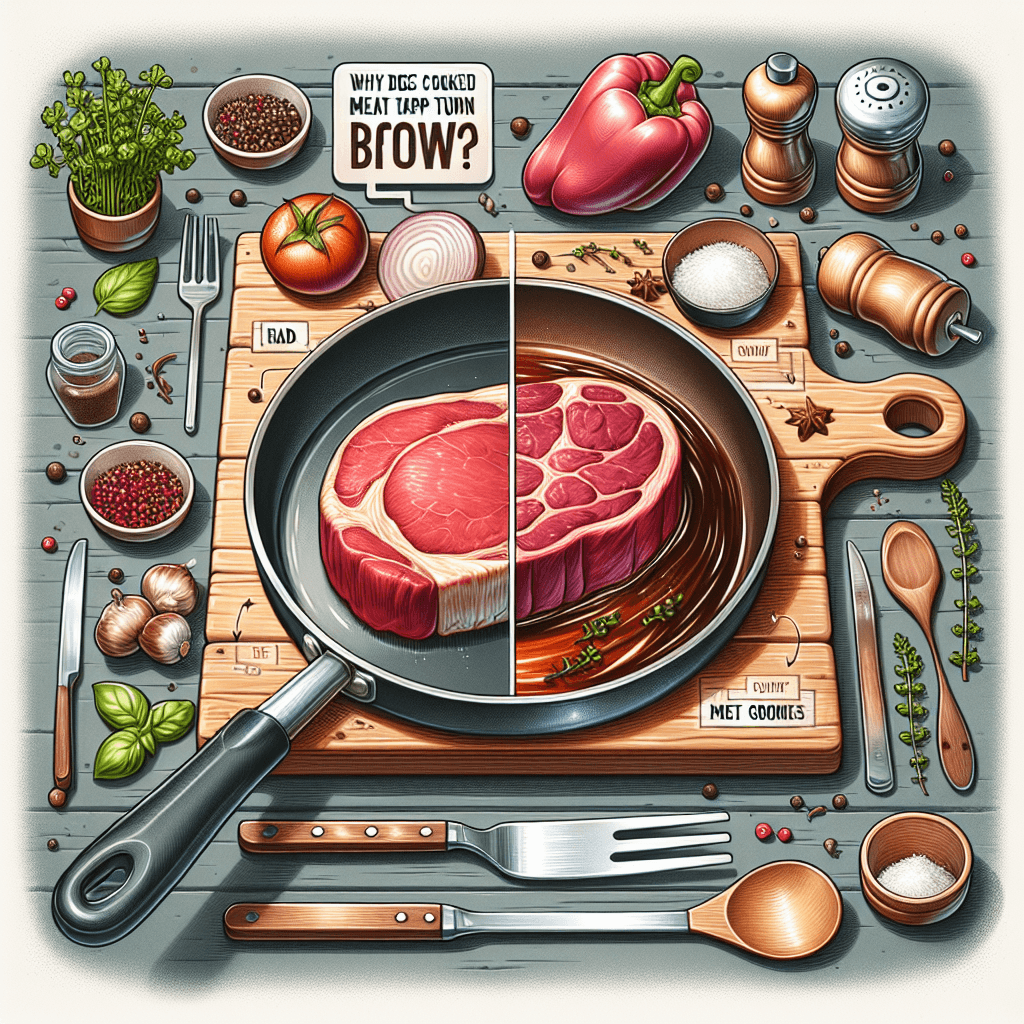

The Sizzling Science: Why Does Cooked Meat Turn Brown

Ever wondered about the transformation your steak undergoes, from vibrant red to a deep, appetizing brown? Uncover the fascinating science behind this universal kitchen phenomenon and the chemical reactions that create that perfect sear.

Too Long; Didn't Read

Cooked meat turns brown due to a chemical transformation that changes its color from raw red to an appetizing brown, creating the familiar and delicious seared crust.

Title: The Sizzling Science: Why Does Cooked Meat Turn Brown?

Introduction

Have you ever paused before taking a bite of a perfectly seared steak or a juicy burger, admiring its rich brown crust, and wondered about the transformation it underwent? From vibrant red in its raw state to a deep, appetizing brown after cooking, this color change is a universal kitchen phenomenon. Understanding why cooked meat turns brown is not just a matter of culinary curiosity; it’s a glimpse into the fascinating chemistry that impacts flavor, texture, and even food safety. This blog post will delve into the scientific processes responsible for this familiar yet complex change, exploring the key molecules and reactions at play.

Main Content

The Star Player: Myoglobin's Color Journey

The primary reason raw meat appears red is due to a protein called myoglobin.

- Myoglobin is found in muscle cells and is responsible for storing oxygen.

- The iron atom within the myoglobin molecule is key to its color.

- Initially, in freshly cut meat with limited oxygen exposure, myoglobin is in its deoxymyoglobin state, giving it a purplish-red hue.

- When exposed to air, the iron in myoglobin binds with oxygen, forming oxymyoglobin, which imparts the familiar bright cherry-red color we associate with fresh meat in the butcher's display.

- Prolonged exposure or lack of oxygen can lead to the formation of metmyoglobin, where the iron atom oxidizes (loses an electron). Metmyoglobin has a brownish-red color, which is why meat can sometimes look less appealing even before cooking if not stored properly.

The Heat is On: Myoglobin Denaturation

When meat is cooked, the heat causes significant changes to its proteins, a process known as denaturation. Myoglobin is no exception.

- Denaturation Defined: Heat disrupts the complex three-dimensional structure of proteins, causing them to unfold and change their properties.

- Impact on Myoglobin: As the temperature of the meat rises during cooking, the myoglobin molecule begins to denature. The iron atom at its core changes its chemical state, oxidizing from the ferrous (Fe2+) to the ferric (Fe3+) state.

- The Brown Result: This altered form of myoglobin is called hemichrome (or denatured globin hemichromogen). It is this compound that is primarily responsible for the tan to brown color seen in the interior of cooked meat. The more thoroughly meat is cooked, the more myoglobin is denatured, leading to a browner, less pink appearance. This is why a well-done steak is brown throughout, while a rare steak retains a red or pink center where myoglobin is less denatured.

Surface Sensation: The Maillard Reaction

While myoglobin denaturation explains the internal color change, the delicious, deep brown crust on well-cooked meat is largely due to a different set of chemical reactions known as the Maillard reaction.

- What it is: Named after French chemist Louis-Camille Maillard, who first described it in the early 20th century, this reaction occurs between amino acids (the building blocks of proteins) and reducing sugars (simple sugars) when heated.

- Temperature is Key: The Maillard reaction typically kicks in at higher temperatures, generally above 285°F (140°C). This is why searing, roasting, grilling, or frying meat produces a browner surface than boiling or steaming.

- More Than Just Color: Beyond creating brown pigments called melanoidins, the Maillard reaction is a flavor powerhouse. It generates hundreds of different aroma and flavor compounds, contributing to the savory, roasted, and complex taste profiles we love in cooked meat. It's distinct from caramelization, which is the browning of sugars alone and occurs at even higher temperatures.

Other Influencing Factors

Several other factors can influence the final color of cooked meat:

- pH: The acidity of the meat can affect the rate and extent of browning.

- Animal Age and Species: Older animals and species like beef tend to have more myoglobin, resulting in a darker raw and cooked color compared to younger animals or species like poultry.

- Curing Agents: The presence of nitrites, often used in cured meats like ham or bacon, reacts with myoglobin to form nitrosylmyoglobin. This compound is heat-stable and retains a pinkish-red color even after cooking, which is why cooked ham stays pink.

Conclusion

The transformation of meat from red to brown upon cooking is a captivating interplay of chemistry. The denaturation of the oxygen-storing protein myoglobin is primarily responsible for the internal color change, as heat alters its structure and the oxidation state of its iron atom. On the surface, the celebrated Maillard reaction between amino acids and sugars at higher temperatures creates that desirable brown crust and a symphony of flavors. Understanding these processes not only satisfies our curiosity but also enhances our appreciation for the science that unfolds in our kitchens every day, turning simple ingredients into delicious meals. Next time you cook meat, you'll know the fascinating science behind its beautiful browning.