Why were chainsaws originally invented to assist with childbirth

Before it was a lumberjack's tool, the chainsaw was a gruesome surgical instrument designed for the most desperate moments of childbirth, and its true story is even more horrifying than you can imagine.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: The original chainsaw was a small, hand-cranked medical tool invented in the late 1700s to cut through a woman's pelvic bone during obstructed labor, making the procedure faster and easier than using a simple knife and saw.

From Delivery Room to Forest: Why Were Chainsaws Originally Invented to Assist with Childbirth?

The roar of a chainsaw likely conjures images of lumberjacks and towering trees, not doctors and a delivery room. The association is so strong that the idea of this powerful tool having a place in medicine seems like a morbid myth. Yet, the startling truth is that the precursor to the modern chainsaw was indeed a medical instrument, invented to aid in one of the most perilous moments of human life: a complicated childbirth. This blog post will uncover the surprising history of this invention, exploring the dire medical circumstances of the 18th century that led to its creation and its evolution from a surgical tool to the machine we know today.

The Grim Reality of 18th-Century Childbirth

Before the advent of modern anesthesia and surgical hygiene, childbirth was fraught with danger for both mother and child. One of the most terrifying complications was obstructed labor, where the baby was unable to pass through the mother's pelvis. When a baby was stuck in the birth canal, doctors had very few—and often gruesome—options.

If the baby had already died, a procedure called a craniotomy might be performed. But if the baby was still alive and a cesarean section was not a viable option (it carried an almost certain death sentence for the mother), doctors would perform a symphysiotomy.

A Gruesome Solution: The Symphysiotomy

A symphysiotomy is a surgical procedure in which the cartilage of the pubic symphysis—the joint connecting the two halves of the pelvis at the front—is severed. This allows the pelvis to widen slightly, creating more space for the baby to pass through.

Before the invention of a specialized tool, this procedure was performed with a simple hand knife and saw. It was an agonizing, slow, and messy process performed on a fully conscious woman. The imprecision of the tools often led to severe damage to internal organs and a long, painful recovery, if the mother survived at all. The medical community desperately needed a way to make this life-saving procedure faster, more accurate, and less traumatic.

Enter the Osteotome: The First "Chainsaw"

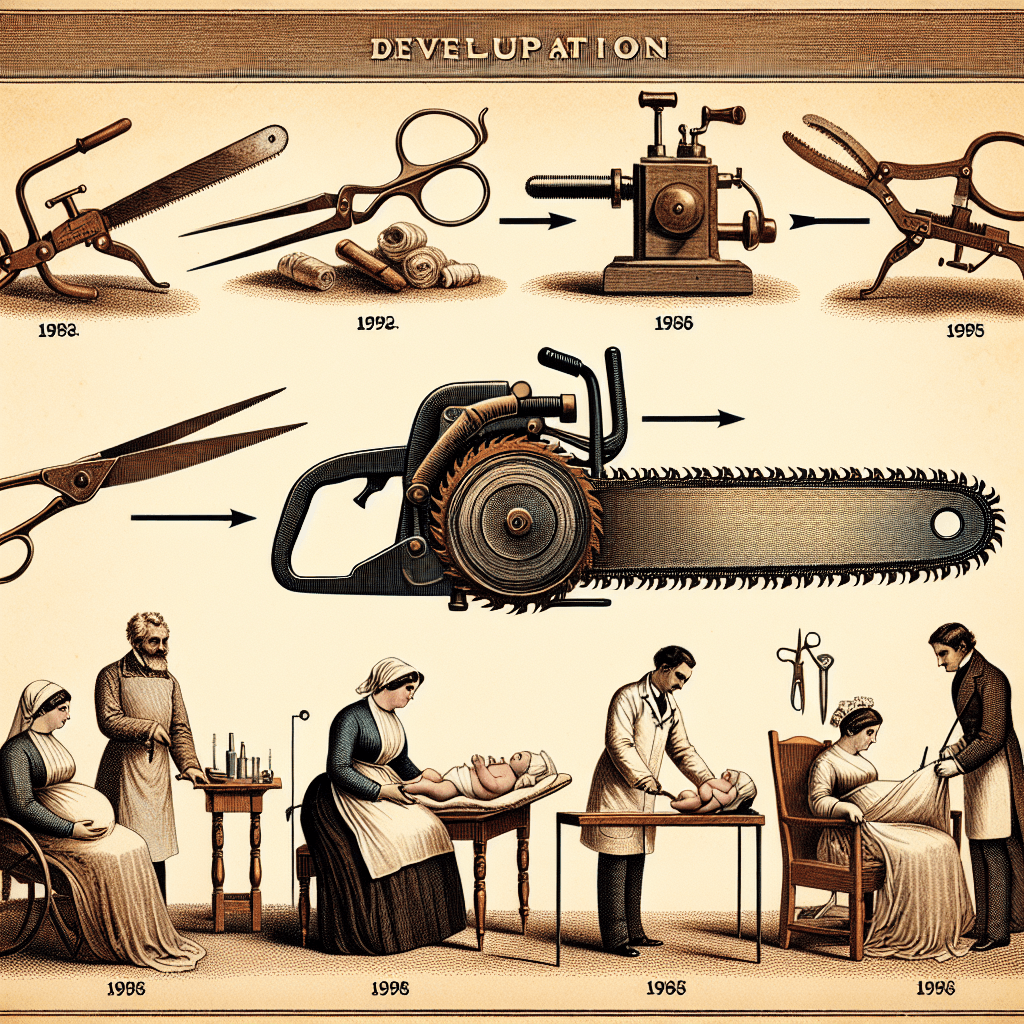

This medical need led two Scottish doctors, John Aitken and James Jeffray, to develop the prototype for the chainsaw in the late 1780s. However, their invention was far from the gas-powered behemoth we picture today. It was a small, hand-cranked device called an osteotome, which translates to "bone cutter."

The osteotome featured a fine chain with serrated cutting links that was guided around a blade. By turning a handle, the surgeon could power the chain, allowing for a much cleaner and quicker cut through the pelvic bone and cartilage than a simple knife could provide. The goal was to minimize pain and improve the chances of a successful outcome for both mother and child.

Key features of the first osteotome included:

- Hand-crank powered: It was operated manually, giving the surgeon precise control.

- Small and precise: It was designed for delicate surgical work, not felling trees.

- A cutting chain: This was the revolutionary concept that would later define the modern chainsaw.

This instrument, while still terrifying by modern standards, was a significant innovation for its time. It represented a step toward making a brutal but necessary procedure more manageable.

The Evolution: From Operating Room to Tool Shed

The medical use of the chain osteotome was relatively brief. The rapid development of anesthesia and antiseptic practices in the 19th century made the C-section a much safer and more widely adopted procedure, rendering the symphysiotomy largely obsolete in most of the developed world.

However, the core concept of a powered cutting chain was too ingenious to disappear. In the 1830s, a German orthopedist named Bernhard Heine developed his own version of the osteotome, further refining the tool for various bone-cutting procedures. The idea slowly began to spread beyond medicine. It wasn't until the early 20th century that the tool made its biggest leap. Innovators like Andreas Stihl in Germany began experimenting with a new power source: the gasoline engine. By attaching an engine to the cutting chain concept, they transformed the delicate surgical instrument into a powerful, portable tool for forestry, and the modern chainsaw was born.

Conclusion

The history of the chainsaw is a powerful reminder of how technology can evolve in unexpected ways to meet different human needs. What began as a desperate attempt to save lives in the delivery room became the tool that revolutionized the logging industry. The hand-cranked osteotome, designed to make childbirth safer, laid the conceptual groundwork for the machine that exists in tool sheds and forests around the globe. So, the next time you hear the distinct buzz of a chainsaw, you can recall its unlikely origins—not in a forest, but in the hands of a surgeon working to bring a new life into the world.