The Chemistry of Nostalgia: What Causes the 'Old Book Smell'

That distinct, slightly sweet aroma of an old book isn't just dust—it's the result of a complex chemical process. Discover the fascinating science behind the smell that evokes powerful feelings of nostalgia and comfort.

Too Long; Didn't Read

The 'old book smell' is caused by the slow chemical decay of paper, ink, and adhesives, which releases a unique blend of volatile organic compounds into the air.

The Chemistry of Nostalgia: What Actually Causes that Distinct "Old Book Smell"?

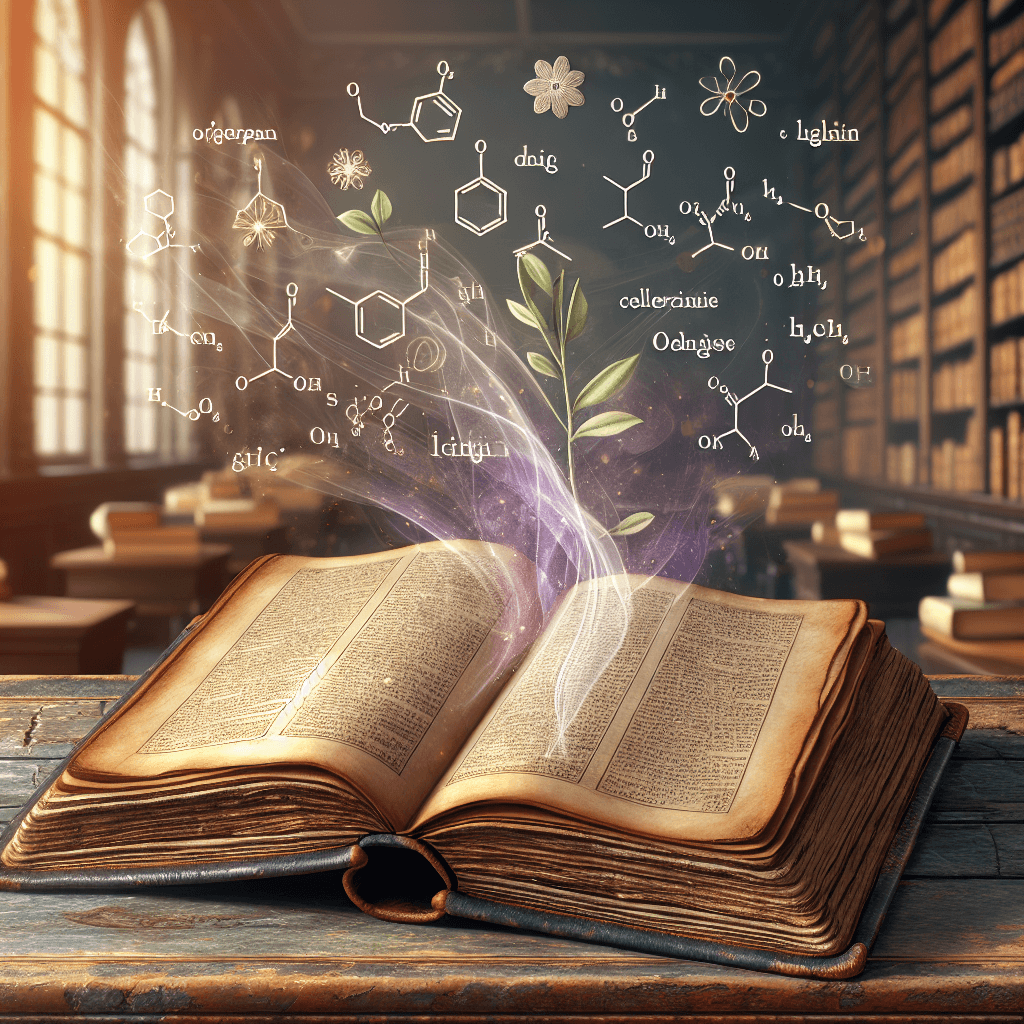

Step into any antiquarian bookshop or library archive, take a deep breath, and you’re instantly greeted by it: that distinct, slightly sweet, sometimes musty aroma we call the "old book smell." For many, it evokes feelings of comfort, nostalgia, and intellectual curiosity. But have you ever wondered what actually causes that unique scent? It’s not just dust or age; it’s a complex chemical process unfolding within the pages. This post dives into the science behind that beloved bibliosmia (the love of the smell of books).

The aroma wafting from an aging book is essentially the smell of organic materials slowly breaking down. Paper, ink, and binding adhesives are all undergoing a gradual process of chemical degradation over time, releasing a cocktail of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) into the air. It's these airborne chemicals that our noses detect, creating the characteristic scent profile we associate with old books. Let's break down the key contributors.

The Aging Ingredients: Paper, Lignin, and Acid

The primary component responsible for the smell is the paper itself. Historically, paper was made from cotton or linen rags, materials high in stable cellulose. However, from the mid-19th century onwards, wood pulp became the dominant source. Wood contains not only cellulose but also a significant amount of lignin – a complex polymer that holds wood fibers together.

Here’s where the chemistry gets interesting:

- Acid Hydrolysis: Over time, acids present in the paper (either residual from manufacturing, absorbed from air pollution, or produced by lignin breakdown) cause cellulose fibers to break down. This process, called acid hydrolysis, weakens the paper and releases various VOCs.

- Lignin Oxidation: Lignin is particularly susceptible to oxidation. As it breaks down, it generates more acids, accelerating cellulose degradation. Crucially, lignin breakdown also releases aromatic compounds closely related to vanilla – a key component of the old book smell. Books printed before the 1850s often lack this strong lignin component and may have a different, less "vanilla-like" aged scent.

Meet the VOCs: The Chemical Signature of Decay

Researchers, particularly those in heritage science like the experts at the UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage, have analyzed the air around old books to identify the specific VOCs responsible for their scent. While the exact blend varies depending on the book's materials and storage history, some common culprits include:

- Vanillin: As mentioned, this comes from lignin breakdown and imparts a distinct vanilla scent.

- Benzaldehyde: Contributes almond-like, slightly bitter notes.

- Furfural: Produced by the degradation of cellulose, often described as having a sweet, bready, or almond-like aroma. Modern paper processing aims to remove precursors that form furfural.

- Toluene and Ethylbenzene: These can lend sweetish, paint-thinner-like odors, sometimes originating from inks or bindings.

- 2-Ethyl Hexanol: May contribute a slightly floral or earthy note.

The unique "old book smell" arises not from a single compound but from the specific combination and concentration of these and dozens of other VOCs. It’s a complex aromatic profile, a chemical fingerprint telling the story of the book's composition and decay.

Factors Shaping the Scent Profile

Not all old books smell the same. Several factors influence the specific aroma:

- Paper Composition: The amount of lignin, the presence of acidic compounds, and the type of sizing used all play a role.

- Binding and Glues: Older books often used animal glues, which degrade differently than modern synthetic adhesives, adding their own VOCs to the mix.

- Inks: Different ink formulations can contribute to or accelerate paper degradation and release their own scents.

- Storage Conditions: Temperature, humidity, and exposure to light and pollutants dramatically affect the rate and type of chemical decay. High humidity can also encourage mold growth, which produces a distinctly unpleasant musty smell quite different from the inherent chemical breakdown scent.

A Whiff of History

The "old book smell," therefore, is far more than just a pleasant scent. It's the tangible, breathable result of chemical reactions silently documenting the book's journey through time. It’s the slow, inevitable decay of organic materials releasing a complex aromatic signature. Scientists can even use VOC analysis as a non-destructive way to assess the condition of old books and documents, helping conservators preserve our written heritage.

So, the next time you pick up an old volume and inhale deeply, take a moment to appreciate the intricate chemistry at play. You're not just smelling paper and ink; you're smelling history itself, one volatile organic compound at a time.