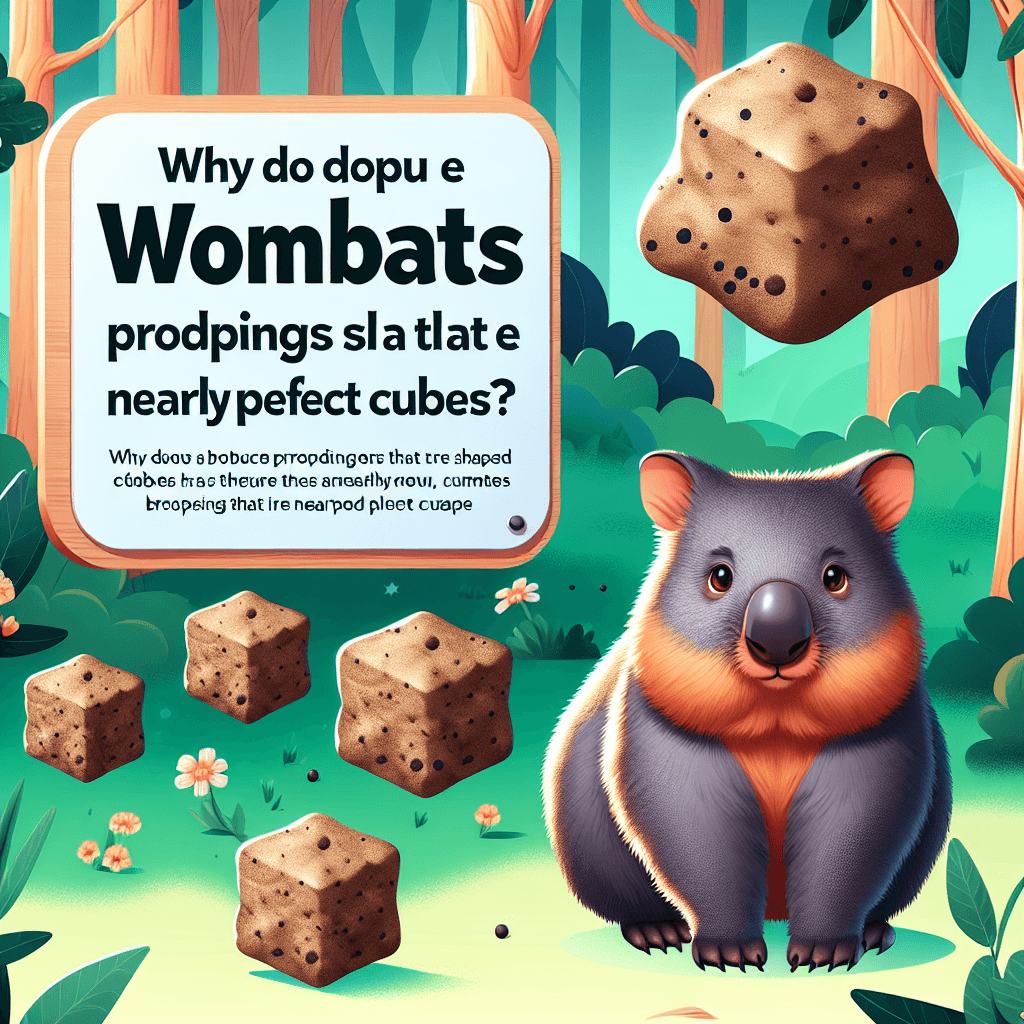

Why do wombats produce droppings that are shaped like nearly perfect cubes

Nature almost never works in straight lines, yet the wombat defies biology by producing perfectly geometric cubes with startling precision. Discover the fascinating evolutionary secret and the high-pressure physics behind the world’s most bizarre digestive feat.

Too Long; Didn't Read

Wombats produce cube-shaped droppings due to the unique, varying elasticity of their intestinal walls. As waste moves through the gut, stiff and flexible sections mold it into cubes. This evolutionary trait prevents the scat from rolling away, allowing the animals to effectively mark their territory on uneven surfaces like rocks and logs.

Nature’s Only Cube: Why do wombats produce droppings that are shaped like nearly perfect cubes?

In the rugged landscapes of Australia, an evolutionary quirk has long puzzled hikers and biologists alike: the presence of small, stackable, and remarkably geometric cubes of animal waste. These "bricks" belong to the wombat, a sturdy, burrowing marsupial that holds the unique distinction of being the only animal in the world known to produce square-shaped scat. For decades, the mechanism behind this biological anomaly remained a mystery. Why do wombats produce droppings that are shaped like nearly perfect cubes, and how does a round anus produce a six-sided shape?

The answer lies in a fascinating intersection of specialized anatomy and territorial survival. By investigating the wombat’s internal biology and environmental needs, researchers have finally unraveled how these animals utilize physics to create nature’s most unusual geometry.

The Mystery of the Intestinal Architecture

For a long time, popular myths suggested that wombats might have square-shaped sphincters or that they manually "patted" their waste into shapes. However, a landmark study led by Patricia Yang and her team at the Georgia Institute of Technology, which won an Ig Nobel Prize in 2019, revealed that the secret is hidden within the final stages of the digestive tract.

Wombats have an exceptionally slow metabolism. It can take anywhere from 8 to 14 days for a meal to pass through their system. During this time, the body absorbs every possible drop of moisture, resulting in waste that is significantly drier and more rigid than that of most mammals. The shaping occurs in the last 17% of the intestine, where the walls are not uniform.

The Role of Muscle Elasticity

Unlike human intestines, which have a consistent thickness and elasticity around the circumference, a wombat’s intestine features two distinct stiff zones and two flexible zones. As the intestine undergoes rhythmic contractions (peristalsis) to move the waste along:

- The Stiff Zones: These areas resist stretching and push back firmly against the dehydrating waste.

- The Flexible Zones: These areas stretch more easily, allowing the corners of the cube to form as the waste is compressed.

As the fecal matter dries out in the colon, these varying levels of tension mold the material into flat faces and sharp edges, maintaining the shape even after the waste is excreted.

Why Shape Matters: A Territorial Tool

In the natural world, biological traits rarely exist without a functional purpose. The cube shape provides a distinct evolutionary advantage for the wombat’s social and territorial behavior. Wombats are solitary and highly territorial animals with poor eyesight but a keen sense of smell. They use their droppings as "scent posts" to communicate with other wombats and mark the boundaries of their range.

Prevention of Rolling

Wombats prefer to leave their droppings on elevated surfaces, such as:

- Large rocks

- Fallen logs

- The mounds of dirt outside their burrows

In these locations, a standard round or cylindrical dropping would likely roll away or be washed away by rain. A cube, however, remains exactly where it is placed. This stability allows the wombat to "stack" its droppings—sometimes up to 20 to 30 in a single prominent location—ensuring that its scent remains at nose level for any passing rivals or potential mates.

Engineering and Medical Implications

Understanding why wombats produce droppings that are shaped like nearly perfect cubes has interests beyond simple curiosity. In the field of manufacturing, "cubing" usually requires expensive molds or cutting tools. The wombat provides a biological model for "soft tissue molding," showing how a soft, tubular structure can create geometric shapes through internal pressure alone. Engineers believe this could eventually lead to new ways of manufacturing 3D structures using soft robotics or advanced polymers.

Conclusion

The question of why wombats produce droppings that are shaped like nearly perfect cubes leads us to a remarkable example of evolutionary adaptation. It is a process driven by a combination of extreme dehydration, unique intestinal muscle distribution, and a strategic need to mark territory in a way that defies gravity.

By producing stable, stackable cubes, the wombat has developed a highly efficient communication system that perfectly suits its environment. This discovery reminds us that even the most peculiar aspects of animal biology serve a purpose, often bridging the gap between complex physics and the simple necessity of survival. For those interested in the wonders of the natural world, the wombat stands as a testament to the creative and unexpected solutions found in the wild.