How can a sea slug eat a jellyfish's stingers and then use them for its own defense

This soft-bodied slug commits the perfect crime, eating a jellyfish's venomous stingers only to wield them as its own deadly defense.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Some sea slugs eat jellyfish and are immune to their stings. They move the unfired stingers through their own digestive system to sacs on their back, storing them to use as a second-hand defense against their own predators.

Stealing the Sting: How Can a Sea Slug Eat a Jellyfish's Stingers and Then Use Them for Its Own Defense?

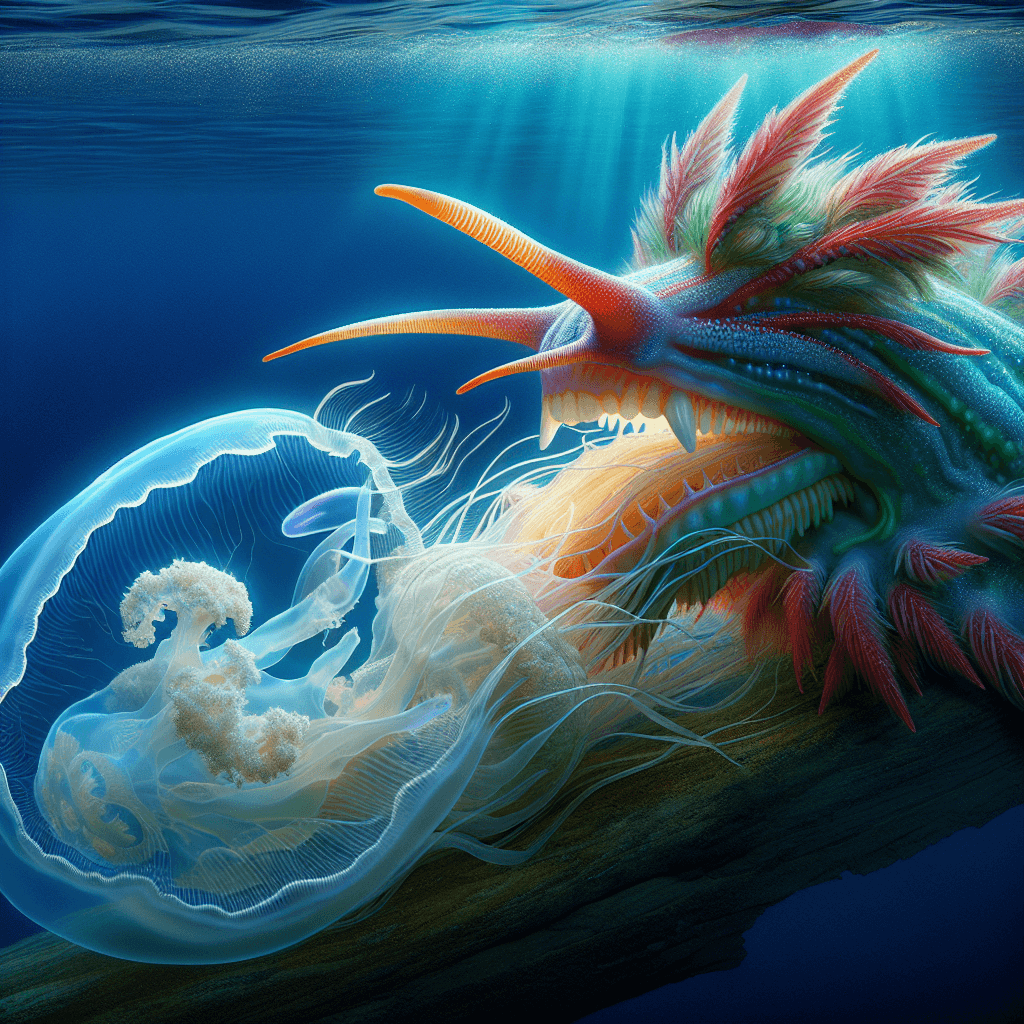

Imagine a creature so soft and slow-moving it looks like a living jewel, yet it arms itself with the microscopic, venomous harpoons of its prey. This isn't science fiction; it's the everyday reality for certain sea slugs. In one of nature's most bizarre and brilliant displays of adaptation, these mollusks consume the deadly stinging cells of jellyfish and sea anemones and repurpose them for their own protection. This post will dive into the fascinating biological process that allows a delicate sea slug to handle, transport, and wield these stolen weapons without harming itself.

The Thief in the Tides: Meet the Nudibranch

The masters of this craft are a group of shell-less sea slugs called aeolid nudibranchs. Known for their breathtaking colors and frilly external appendages called cerata, they appear to be some of the most vulnerable inhabitants of the reef. Lacking a protective shell and moving at a glacial pace, they should be an easy meal for any passing fish. However, their vibrant colors often serve as a warning sign to predators, advertising a well-armed and unpalatable bite, thanks to their remarkable diet of venomous creatures like jellyfish, hydroids, and sea anemones.

A Dangerous Dinner: Swallowing a Weapon

The first challenge for the nudibranch is eating its prey without falling victim to the very weapons it seeks to steal. Jellyfish and their relatives are armed with thousands of specialized stinging cells called cnidocytes, each containing a coiled, harpoon-like structure known as a nematocyst. When triggered by touch, these nematocysts fire at incredible speed, injecting venom into a target.

So, how does the soft-bodied slug avoid this? It employs several clever strategies:

- Protective Mucus: The nudibranch secretes a thick layer of protective mucus around its mouth and throughout its digestive tract. This coating acts as a chemical shield, preventing most of the nematocysts from recognizing the slug as a threat and firing.

- Selective Consumption: Research suggests that nudibranchs are particularly adept at consuming immature nematocysts. These developing cells are not yet capable of discharging, making them safe to swallow and ideal for later use.

From Stomach to Skin: The Journey of a Stolen Weapon

Once ingested, the real magic begins. This process, known as kleptocnidy (from the Greek kleptes for "thief" and knide for "nettle"), is a masterclass in biological engineering.

The undigested, unfired nematocysts are carefully separated from the rest of the jellyfish tissue. Instead of being broken down for nutrients, they are transported through specialized ciliated tubes that branch off from the stomach. These tubes extend all the way into the nudibranch’s cerata—those finger-like projections on its back.

At the very tips of these cerata are specialized storage sacs called cnidosacs. Here, the stolen nematocysts are meticulously packed and stored, facing outwards, ready for deployment. The slug essentially becomes a living arsenal, its back lined with microscopic, venom-filled harpoons. When a predator, like a fish, attempts to bite the nudibranch, the pressure causes the cnidosacs to contract, firing the nematocysts and delivering a painful, venomous sting that quickly teaches the attacker to seek an easier meal elsewhere.

An Evolutionary Masterstroke

This incredible adaptation is more than just simple recycling. Studies have shown that some nudibranchs are highly selective, preferentially storing the most powerful and effective types of nematocysts from their prey while digesting the weaker ones. This ability to choose the best weapons for the job highlights a sophisticated evolutionary relationship between predator and prey. The nudibranch has turned its primary food source into its personal bodyguard, transforming a seemingly huge disadvantage—its soft, slow body—into a formidable defensive advantage.

Conclusion

The ability of a sea slug to eat a jellyfish’s stingers and use them for defense is a testament to the ingenuity of evolution. Through a combination of protective mucus, careful transport, and specialized storage, the nudibranch turns a dangerous meal into a life-saving shield. It’s a perfect example of how survival in the ocean isn't always about being the biggest or the fastest, but sometimes, it’s about being the cleverest. This remarkable process reminds us that even the most delicate-looking creatures can harbor astonishing secrets and complex survival strategies, waiting to be discovered beneath the waves.