What causes some alpine snow to turn pink and smell faintly of watermelon

It's not a magical dessert or a strange chemical spill; the secret behind this pink, watermelon-scented snow is actually alive.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Pink, watermelon-scented snow is caused by a bloom of microscopic algae. The red color is a natural sunscreen the algae produces to protect itself from intense UV radiation at high altitudes.

The Mystery of Watermelon Snow: What Causes Some Alpine Snow to Turn Pink and Smell Faintly of Watermelon?

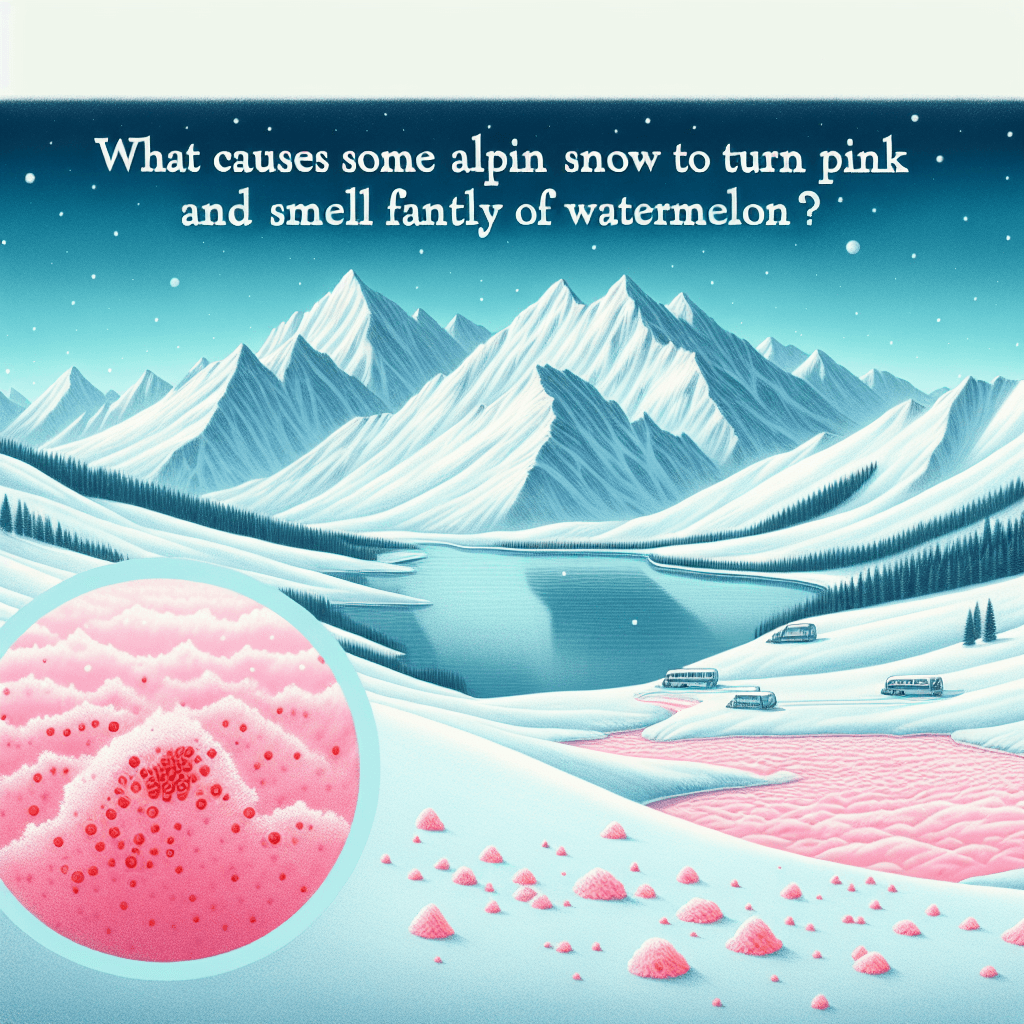

Imagine hiking high in the mountains on a summer day. You expect pristine white snowfields, but instead, you come across a strange and beautiful sight: vast patches of snow blushed with a distinct pink or reddish hue. As you get closer, you notice a faint, sweet scent, surprisingly similar to fresh watermelon. Is this a geological anomaly? A trick of the light? This fascinating phenomenon, known to mountaineers and scientists as "watermelon snow," is no illusion. This post will uncover the microscopic secret behind what causes some alpine snow to turn pink and smell faintly of watermelon.

It's Not Magic, It's Algae

The surprising culprit behind this colorful display is a species of single-celled green algae called Chlamydomonas nivalis. This might seem paradoxical—a green alga that turns snow red—but the explanation lies in its incredible adaptation to one of Earth's most extreme environments.

These microscopic organisms are cryophilic, meaning they thrive in freezing conditions. They lie dormant in the snow and ice during the harsh winter months. When spring and summer arrive, bringing increased sunlight and surface meltwater, the algae spring to life. They reproduce in the liquid water between snow crystals, creating dense "blooms" that can color entire snowfields. While early explorers and mountaineers were mystified by the phenomenon, scientists now understand the biological processes at play.

Why Pink? The Algae's Natural Sunscreen

The key to the pink coloration is a powerful protective pigment. While Chlamydomonas nivalis is technically a green alga containing chlorophyll for photosynthesis, it also produces a bright red carotenoid pigment called astaxanthin.

In the intense, high-altitude environment, the sun's ultraviolet (UV) radiation is incredibly strong and can damage a cell's DNA and photosynthetic apparatus. To protect itself, the alga produces vast amounts of astaxanthin, which acts as a potent natural sunscreen. This secondary red pigment effectively shields the cell's delicate chlorophyll from harmful UV rays. The astaxanthin is so concentrated that it completely masks the underlying green of the chlorophyll, giving the algae—and the snow it inhabits—its characteristic pink to deep-red appearance.

A Whiff of Summer: The Watermelon Scent Explained

The faint, sweet smell of watermelon is another hallmark of this phenomenon. While the exact chemical composition is complex, scientists believe the scent is a byproduct of the algae's metabolic processes. The smell is likely caused by a mixture of volatile organic compounds, including esters, which the algae produce as part of their life cycle. Although it may smell tempting, experts advise against eating watermelon snow. It can harbor bacteria and other microorganisms from the snowpack and is known to have a laxative effect.

More Than Just a Pretty Color: The Environmental Role

Watermelon snow is more than just a beautiful natural curiosity; it plays a significant role in its ecosystem and has broader implications for our climate.

- Accelerated Snowmelt: White snow has a high albedo, meaning it reflects most of the sun's energy back into space. The red pigments in the algae darken the snow's surface, lowering its albedo. This darker surface absorbs more solar radiation, which warms the snow and accelerates the melting process.

- A Climate Feedback Loop: This creates a feedback loop. As the snow melts faster, it creates more liquid water, which provides a better environment for the algae to grow. More algae lead to an even darker surface, which causes even faster melting. According to studies from institutions like the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, these algal blooms can increase snowmelt rates by over 15%.

- A Foundational Food Source: In the seemingly barren alpine environment, Chlamydomonas nivalis forms the base of a simple food web, providing essential nutrients for other specialized organisms like ice worms and snow fleas.

Conclusion

What causes some alpine snow to turn pink and smell faintly of watermelon is a testament to the resilience and adaptability of life. The vibrant color isn't a stain but a living bloom of the alga Chlamydomonas nivalis, which uses a red pigment as a sunscreen against harsh UV radiation. This beautiful phenomenon is also a powerful environmental indicator, playing a direct role in the rate of glacial and snowpack melt. So, the next time you're in the high country and spot a pink snowfield, you'll know you're witnessing a microscopic marvel with a massive impact on its alpine home.