What creates the perfectly smooth holes you sometimes find in beach stones

It's not the endless churn of water that drills these flawless holes, but the lifelong work of a tiny, rock-boring sea creature.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: The smooth holes are made by rock-boring clams or mollusks that grind into softer stones on the seabed to create a permanent home. When they die, the empty, hole-filled rock can wash ashore.

The Ocean's Tiny Drills: What Creates the Perfectly Smooth Holes You Sometimes Find in Beach Stones?

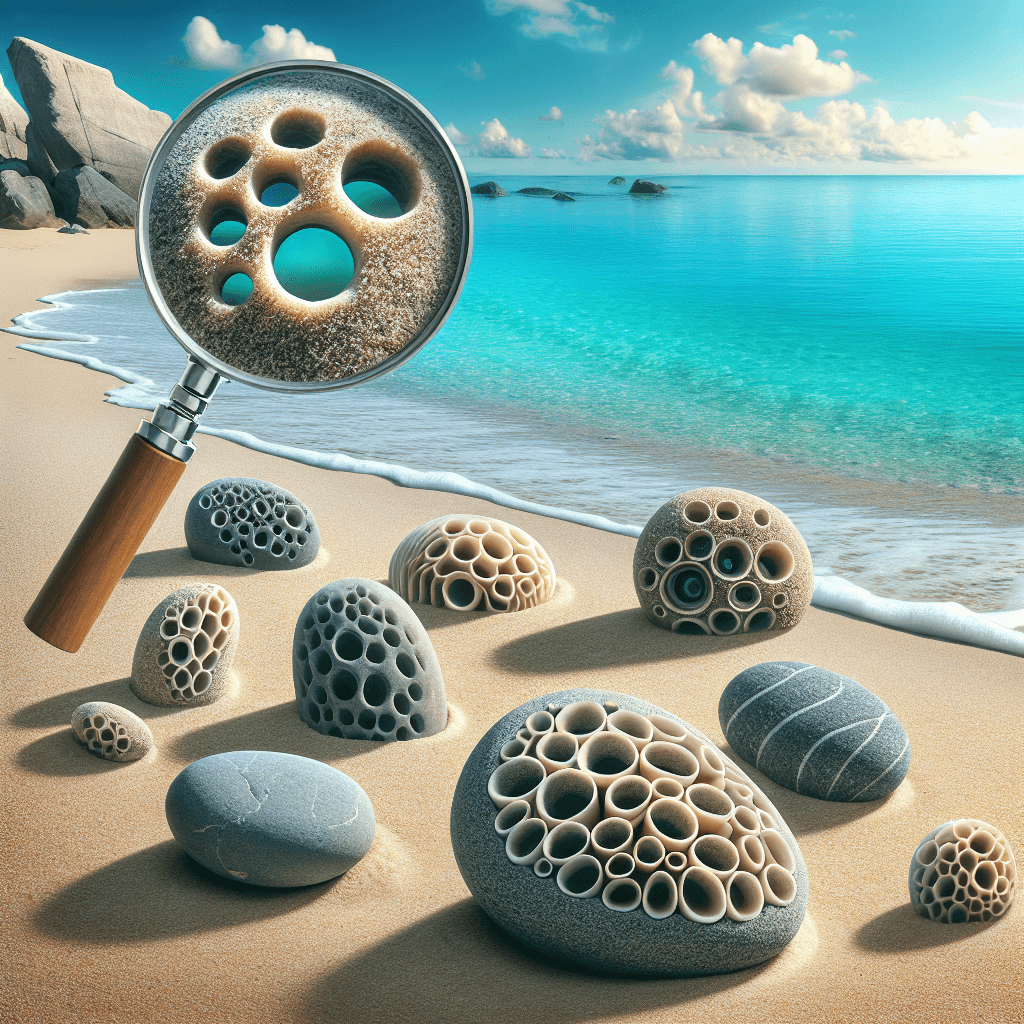

Have you ever strolled along a shoreline, scanning the endless pebbles, and stopped to pick up a special one—a stone with a perfectly smooth, circular hole drilled right through it? These enchanting stones, sometimes called hag stones or witch stones, feel like rare treasures. It’s easy to imagine they were shaped by the endless, random tumbling of the waves, but the truth is far more precise and fascinating. The perfectly smooth holes you find in beach stones are not an accident of erosion, but the deliberate work of a tiny, industrious marine creature. This post will uncover the identity of nature's master stonemason and reveal the remarkable process behind its craft.

The Surprising Sculptor: A Boring Bivalve

The primary culprit behind these perfectly drilled stones is not the water, but a group of clams known as boring bivalves. Specifically, members of the Pholadidae family, commonly called piddocks or angelwings, are the architects of these holes.

These remarkable mollusks don't eat rock. Instead, they create burrows in soft stone like sandstone, mudstone, or chalk to create a safe, permanent home, protecting them from predators and the harsh, churning environment of the intertidal zone. They are pioneers of a process known as bioerosion—the erosion of hard ocean substrates by living organisms. The smooth, uniform hole you see in a beach stone is the lifelong home and final tomb of one of these incredible creatures.

A Masterclass in Bioerosion

So, how does a soft-bodied clam drill through solid rock? The piddock has evolved a brilliant two-part method that combines mechanical force with, in some cases, a bit of chemistry.

The main tool is its own shell. A piddock’s shell is specially adapted with sharp, file-like ridges and spines on its front end. The process works like this:

- Anchoring: The clam extends a muscular organ called a "foot" to anchor itself securely to the bottom of its burrow.

- Grinding: It then contracts its muscles to pull the shell inward, twisting and rocking it back and forth. The serrated edges of the shell grind against the rock, scraping away fine particles much like a drill bit.

- Clearing: The clam uses a siphon to flush the rock dust and debris out of its burrow.

This relentless grinding action, repeated over the clam's lifetime, creates a perfectly smooth, often tapered, hole. The burrow is typically wider at the opening and narrows toward the bottom, mirroring the shape of the piddock's shell as it grew. Once it starts drilling as a juvenile, the piddock is imprisoned for life; as it grows, it enlarges its home but becomes too large to ever leave through the entrance.

The Journey to the Shore

The story doesn't end when the piddock dies. After its life is over, the soft body and fragile shell of the clam decompose, leaving behind the empty, masterfully crafted burrow.

Over time, the rock, often riddled with numerous piddock burrows, is weakened. The relentless force of waves eventually breaks these rocks apart, freeing the fragments. These pieces, each containing the ghost of a piddock's home, are then tumbled in the surf. This final stage of the process wears down the stone's sharp edges and further polishes the hole, resulting in the smooth, beautiful treasure you eventually find washed up on the beach.

Distinguishing Piddock Holes from Other Pits

While piddocks are the primary source of these perfect holes, other natural forces can create imperfections in stones. However, you can usually tell the difference:

- Random Water Erosion: Tends to create irregular pits and crevices, not smooth, uniform, circular tunnels.

- Boring Sponges: Create a network of much smaller, interconnected holes, giving the rock a pockmarked, sponge-like appearance.

- Marine Worms: Can also drill into rock, but their burrows are typically much smaller in diameter and less perfectly rounded.

The signature of a piddock is that single, smooth, and often tapered hole—a clear sign of a creature that once called that stone its home.

A Story Written in Stone

The next time you’re walking on a beach and find one of these holed stones, take a moment to appreciate its incredible origin. It’s more than just a pretty rock; it’s a natural artifact that tells a story of life, engineering, and the powerful, patient forces of the ocean. That perfectly smooth hole is a testament to a tiny mollusk that spent its entire life slowly, meticulously carving a fortress for itself. You are holding the beautiful remnant of a home, created by one of nature’s most surprising and skilled sculptors.