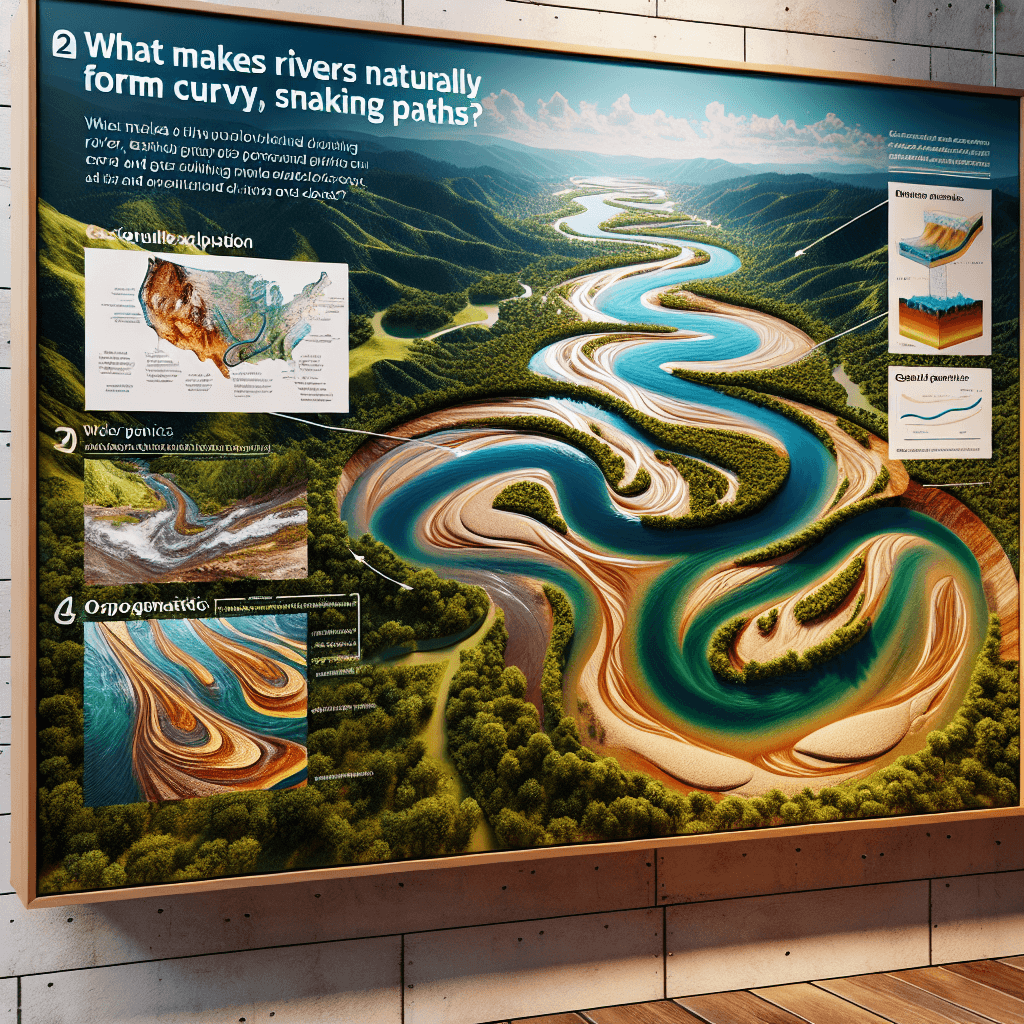

What makes rivers naturally form curvy, snaking paths

The shortest distance between two points may be a straight line, but not for a river. Discover the beautiful chaos that forces water to abandon the straight and narrow for its iconic, winding path.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Water flows faster on the outside of a river bend, eroding the bank, while slower water on the inside deposits sediment. This process continuously exaggerates any small curve, causing the river to snake and meander over time.

Nature's Serpentine Sculptors: What Makes Rivers Naturally Form Curvy, Snaking Paths?

Have you ever gazed at a map or looked down from a plane and wondered why so few rivers run in a perfectly straight line? Instead, they carve mesmerizing, winding patterns across the landscape. These elegant S-shaped curves, known to geologists as meanders, aren't random; they are the result of a beautiful and powerful dance between water, sediment, and the laws of physics. The tendency for a river to curve is so fundamental that even a small trickle of water flowing down a sandy slope will begin to form tiny meanders. This post will explore the fascinating science that explains what makes rivers naturally form their iconic curvy, snaking paths.

The Simple Start of a Complex Curve

A river flowing across a relatively flat plain, or floodplain, doesn't start out with the intention to curve. Its journey from a straight channel to a winding one begins with a simple disturbance. This could be anything that slightly disrupts the uniform flow of water:

- A fallen tree partially blocking the channel.

- A large, resistant boulder on the riverbed.

- A section of the bank that is slightly softer and more easily eroded than the rest.

This minor obstacle is all it takes to deflect the main current, or thalweg, towards one side of the bank. This single, small change sets in motion a self-reinforcing process that will amplify the bend over centuries.

The Dance of Erosion and Deposition

Once the water is pushed to one side, simple physics takes over. As the water flows around the newly forming bend, it behaves much like a car taking a turn. The water on the outside of the bend is forced to travel a longer distance and therefore moves faster. This faster-moving water has more energy.

- On the Outer Bend: The high-energy water scours and erodes the riverbank. This constant erosion creates a steep, cliff-like feature known as a cut bank.

- On the Inner Bend: The water on the inside of the curve travels a shorter distance and moves more slowly. This sluggish water has less energy and can no longer carry all its sediment (sand, silt, and gravel). It deposits this material on the inside of the bend, forming a gently sloping area called a point bar.

This dual process—erosion on the outside and deposition on the inside—is the engine of meandering. The cut bank deepens and carves the curve outward, while the point bar builds inward, effectively causing the meander to migrate across the floodplain over time.

The Lifecycle of a Meander: From Bend to Oxbow Lake

This process of accentuating curves doesn't go on forever. As the meanders become more and more exaggerated, the "neck" of land between two adjacent bends gets progressively narrower. Eventually, during a major flood or high-water event, the river will seek the most efficient, shortest path. It will breach the narrow neck of land, cutting a new, straighter channel.

Once the new channel is established, the river abandons its old, looping path. Sediment dropped by the river seals off the ends of the old loop, isolating it from the main flow. This abandoned, crescent-shaped meander, now filled with still water, becomes a new landmark: an oxbow lake. These lakes are common features in mature river valleys and serve as a beautiful, lasting monument to the river's former path.

Factors Influencing the Wiggle

While the process is universal, the exact shape and size of meanders are influenced by several factors:

- Gradient: Rivers flowing across gentle slopes with low gradients are far more likely to meander. Steep, fast-flowing mountain streams have too much energy and tend to carve straight down into the bedrock rather than side-to-side.

- Bank Composition: The material of the riverbanks plays a crucial role. Banks made of soft, unconsolidated silt and sand are easily eroded, allowing for rapid and dramatic meandering. In contrast, banks composed of tough bedrock will resist erosion and keep the channel relatively straight.

- Sediment Load: The amount and type of sediment a river carries influence how quickly point bars build up, affecting the overall dynamics of the meander's migration.

Conclusion

The snaking path of a river is far from a random quirk of nature. It is a logical and predictable outcome of water following the path of least resistance, governed by the fundamental forces of erosion and deposition. From a single disturbance in its flow, a river begins a continuous process of carving and building that sculpts the landscape, creating diverse habitats and fertile floodplains. The next time you see a winding river or spot an oxbow lake on a map, you’ll recognize it not as a simple line, but as a dynamic and ever-evolving masterpiece of natural engineering.