Why are the winds on old maps drawn as puffy-cheeked faces

Those puffy-cheeked faces blowing storms on antique maps aren't just quaint decoration; they're a fascinating glimpse into a time when mythology, not meteorology, was used to chart the world.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Ancient cultures personified winds as gods, and early cartographers adopted this artistic tradition. The puffy-cheeked faces were a clear and decorative visual shorthand to show the direction and force of the wind on maps.

Mapping the Invisible: Why Are the Winds on Old Maps Drawn as Puffy-Cheeked Faces?

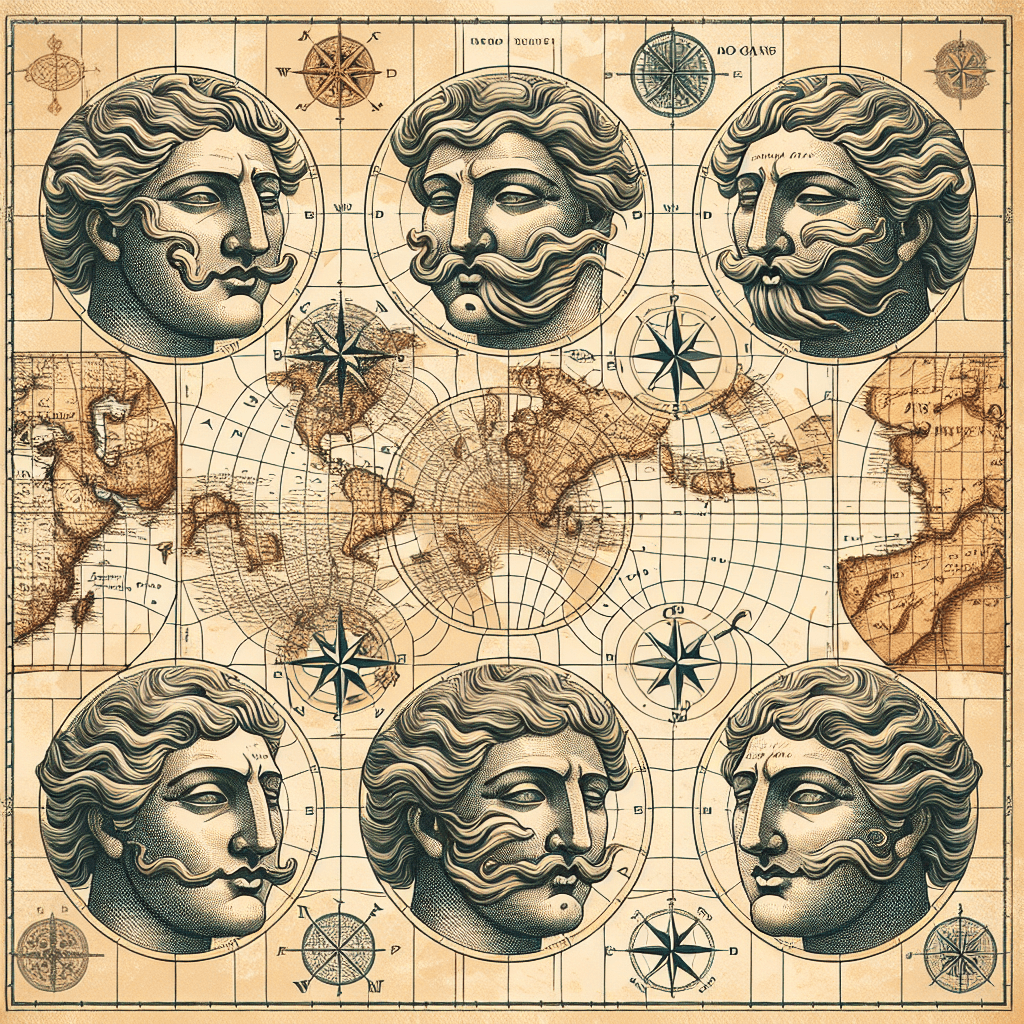

Ever gazed upon a centuries-old map, with its faded coastlines and fantastical sea monsters, and noticed the curious, cherubic faces puffing their cheeks from the corners? These illustrations, often called "wind heads," are far more than quaint decorations. They represent a fascinating intersection of mythology, early science, and artistry, revealing how our ancestors visualized and made sense of the invisible forces that shaped their world. This post will journey back in time to uncover the historical, practical, and artistic reasons behind this unique cartographic tradition.

The Breath of the Gods: Mythological Roots

Long before meteorology could explain atmospheric pressure and jet streams, ancient civilizations personified the winds as powerful deities. The most influential of these were the Greek Anemoi, the gods of the four directional winds:

- Boreas: The cold, harsh North Wind.

- Zephyrus: The gentle, life-giving West Wind.

- Notus: The stormy, wet South Wind.

- Eurus: The unlucky, tempestuous East Wind.

Early cartographers, heavily influenced by classical knowledge, adopted this tradition. Drawing the winds as faces—often with expressions reflecting their character—made the abstract concept of wind tangible and relatable. A scowling, bearded Boreas visually communicated the dangers of a northern gale, while a serene Zephyrus promised a calm and favorable journey. This personification wasn't just artistic flair; it was a way of encoding vital, experience-based knowledge about the world's natural forces onto the map itself.

More Than Just Decoration: A Navigational Tool

While rooted in myth, wind heads served a critical, practical purpose for sailors and explorers. Before the compass rose was universally adopted, these personified winds were a primary method for indicating direction. The direction the face was blowing from was the key piece of information. The puffy cheeks, with air visibly streaming from the mouth, left no doubt about the force and origin of the wind.

These illustrations were essential elements of the "wind rose," a diagram showing the 8, 12, or even 32 principal winds. For a mariner planning a voyage across the Mediterranean, knowing the direction of the prevailing winds was a matter of life and death. The wind heads acted as an intuitive, visual guide, helping sailors orient their maps and anticipate the weather conditions they were likely to encounter. The famous "Tower of the Winds" in Athens, an ancient octagonal clocktower, is a stone testament to this system, with each face depicting one of the eight wind deities.

Filling the Voids: The Artistry of Early Mapmaking

Beyond mythology and navigation, wind heads also served an aesthetic purpose born from a principle known as horror vacui, or the "fear of empty spaces." Early world maps often contained vast, unexplored regions, particularly over the oceans. Rather than leaving these areas blank, which might suggest a lack of knowledge or skill, mapmakers filled them with elaborate illustrations.

Alongside sea serpents, mermaids, and grand ships, wind heads added visual richness and a sense of authority to the map. They transformed a purely functional document into a masterpiece of art and craftsmanship. A beautifully rendered map, complete with detailed wind heads, was not only more valuable but also conveyed the cartographer's world-class skill and knowledge, inspiring confidence in the user.

As the Age of Enlightenment dawned, cartography shifted towards a more empirical and scientific approach. The compass rose, with its clean lines and simple letters (N, S, E, W), became the standardized and more precise tool for indicating direction. The beautiful, personified winds were gradually seen as archaic and unscientific, and they slowly vanished from maps, replaced by the abstract symbols we use today.

Conclusion

The puffy-cheeked faces blowing from the corners of old maps are powerful relics of a time when art, myth, and science were inextricably linked. They began as representations of ancient gods, evolved into vital navigational aids for sailors, and served as beautiful artistic elements that brought maps to life. While they have been replaced by more modern conventions, they remain a charming window into our ancestors' worldview. So, the next time you see one, remember you're not just looking at a quaint decoration—you're seeing a story of how humanity first learned to chart the invisible forces of the wind.