Why can a wasp sting you repeatedly, but a honeybee dies after just one

It's not about anger, it's about anatomy; discover the fatal design flaw that turns a honeybee's sting into a suicide mission, while a wasp lives to sting another day.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: A honeybee's stinger is barbed, so it gets stuck in your skin and rips out its own guts, killing it. A wasp's stinger is smooth like a needle, so it can sting you repeatedly.

Sting Anatomy 101: Why a Wasp Can Sting Repeatedly, But a Honeybee Dies After Just One?

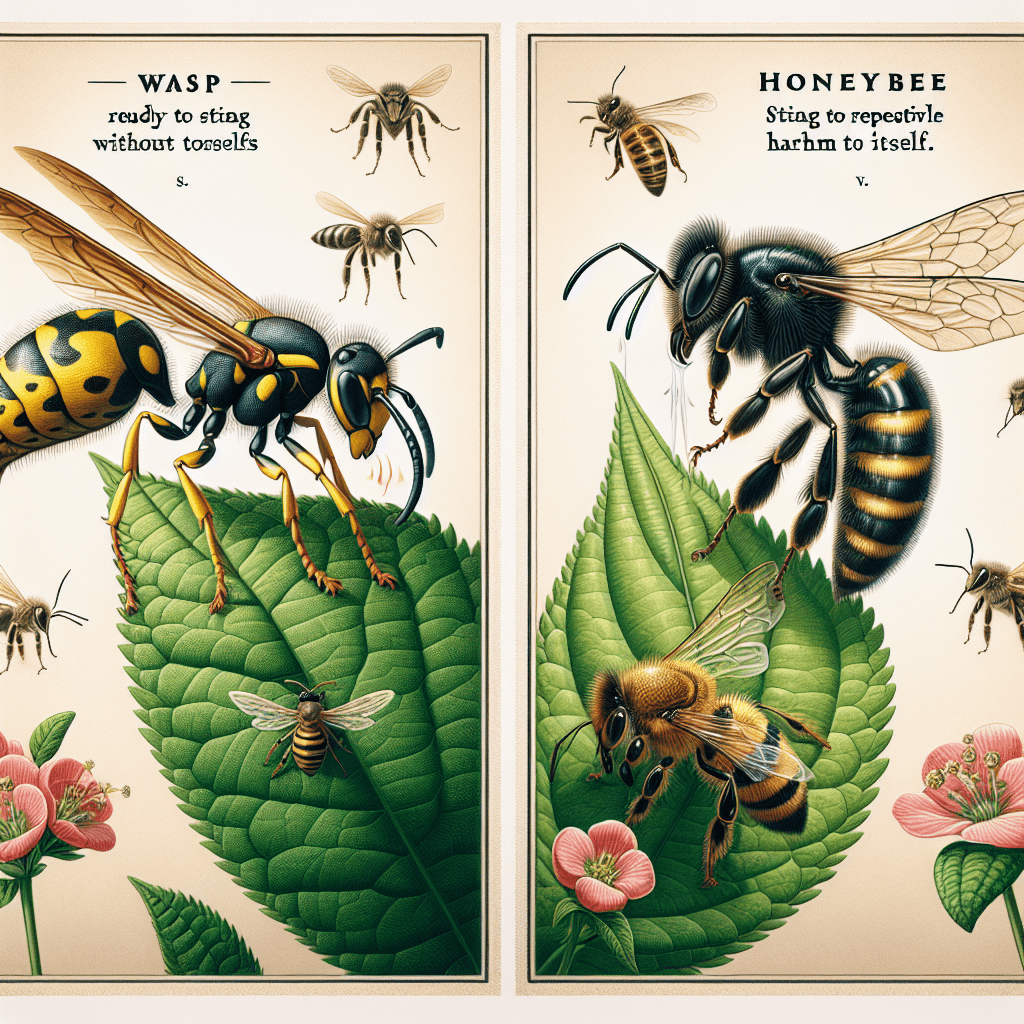

It’s a familiar summer scene: a buzzing insect gets a little too close, and panic sets in. But not all stings are created equal. If you’re unlucky enough to be stung by a wasp, it may come back for a second or third jab. A honeybee, however, makes the ultimate sacrifice, dying after delivering a single, defensive sting. This stark difference isn't a matter of temperament, but a fascinating tale of evolutionary anatomy and survival strategy. Understanding this distinction can change how you see these common, and often misunderstood, insects. This post will delve into the precise anatomical and evolutionary reasons behind the honeybee's final act and the wasp's repeatable attack.

The Honeybee’s Final Act: A Barbed Stinger

The key to the honeybee’s one-time sting lies in the microscopic structure of its stinger, or ovipositor. A worker honeybee’s stinger is not a simple needle; it’s a complex, barbed apparatus. Imagine a tiny harpoon with backward-facing hooks.

When a honeybee stings a target with thick, elastic skin—like a human or another mammal—these barbs anchor the stinger firmly in the flesh. As the bee tries to fly away, it cannot pull the stinger out. The struggle results in a catastrophic injury for the bee. It is forced to leave behind not only its stinger but also a part of its digestive tract, muscles, and nerves. This self-evisceration, known as autotomy, is fatal, and the bee dies shortly after.

Interestingly, this gruesome outcome is a highly effective defensive strategy. The abandoned stinger has its own nerve ganglion and muscle attachments that continue to pump venom from the attached venom sac into the victim for several minutes, maximizing its impact and releasing an alarm pheromone that signals other bees to the threat.

The Wasp's Weapon: A Smooth, Reusable Dagger

A wasp’s stinger, in contrast, is anatomically different. It is shaped more like a smooth, sharp needle. When a wasp stings, its stinger penetrates the skin and can be withdrawn easily without harming the wasp. This allows it to sting its target multiple times if it continues to feel threatened.

This difference in anatomy is directly linked to the wasp's lifestyle. Unlike honeybees, which are primarily herbivores collecting nectar and pollen, many wasps are predators and scavengers. Their stinger serves two primary purposes:

- Defense: To protect themselves and their nest from threats.

- Hunting: To paralyze prey, such as spiders or caterpillars, which they then feed to their developing young.

A single-use stinger would be evolutionarily inefficient for an insect that needs to hunt repeatedly to provide for its offspring. The ability to sting, retract, and sting again is essential for its survival and role in the ecosystem.

An Evolutionary Tale: Different Lifestyles, Different Tools

The divergence in stinger anatomy is a perfect example of how evolution shapes tools for specific jobs. The survival of these two insects is based on entirely different strategies.

-

The Honeybee (The Superorganism): A honeybee colony functions as a "superorganism." The survival of the individual worker bee is secondary to the survival of the queen and the colony as a whole. A worker bee is one of tens of thousands, and her suicidal sting is an effective last-ditch defense to protect the hive’s vast resources (honey, pollen, and brood) from large predators like bears or badgers. The ultimate sacrifice of one bee is a small price to pay for the colony's continuation.

-

The Wasp (The Individual): Most wasps operate with a greater degree of individuality, even those in social colonies. They must hunt and defend themselves throughout their lives. Losing their stinger after a single use would be a death sentence, preventing them from gathering food or defending against future threats.

It's also worth noting that not all bees die after stinging. Bumblebees, for instance, have smooth stingers similar to wasps and can sting repeatedly. The queen honeybee also has a barbless stinger, but she reserves it for fighting rival queens within the hive.

Conclusion

The answer to why a wasp can sting repeatedly while a honeybee dies lies in a single, crucial anatomical detail: a smooth stinger versus a barbed one. This difference is not a random quirk of nature but a finely tuned evolutionary adaptation tied directly to each insect's role and survival strategy. The honeybee's barbed stinger is a sacrificial tool of ultimate defense for the colony, while the wasp's smooth stinger is a reusable weapon for a life of hunting and self-preservation. So, the next time you see one of these buzzing insects, you can appreciate the complex evolutionary story behind its powerful, and very different, sting.