Why did Napoleon's soldiers' buttons turn to dust in the freezing Russian cold

It wasn't just the cannons or the Cossacks that defeated the Grande Armée; the unraveling of Napoleon's empire may have started with a bizarre chemical reaction in the very buttons holding their coats together.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: The soldiers' buttons were made of tin. In the extreme Russian cold, the tin suffered from tin pest, a process where the metal transforms into a brittle, crumbly powder, causing their uniforms to fall apart.

Tin Pest and Tragedy: Why Did Napoleon's Soldiers' Buttons Turn to Dust in the Freezing Russian Cold?

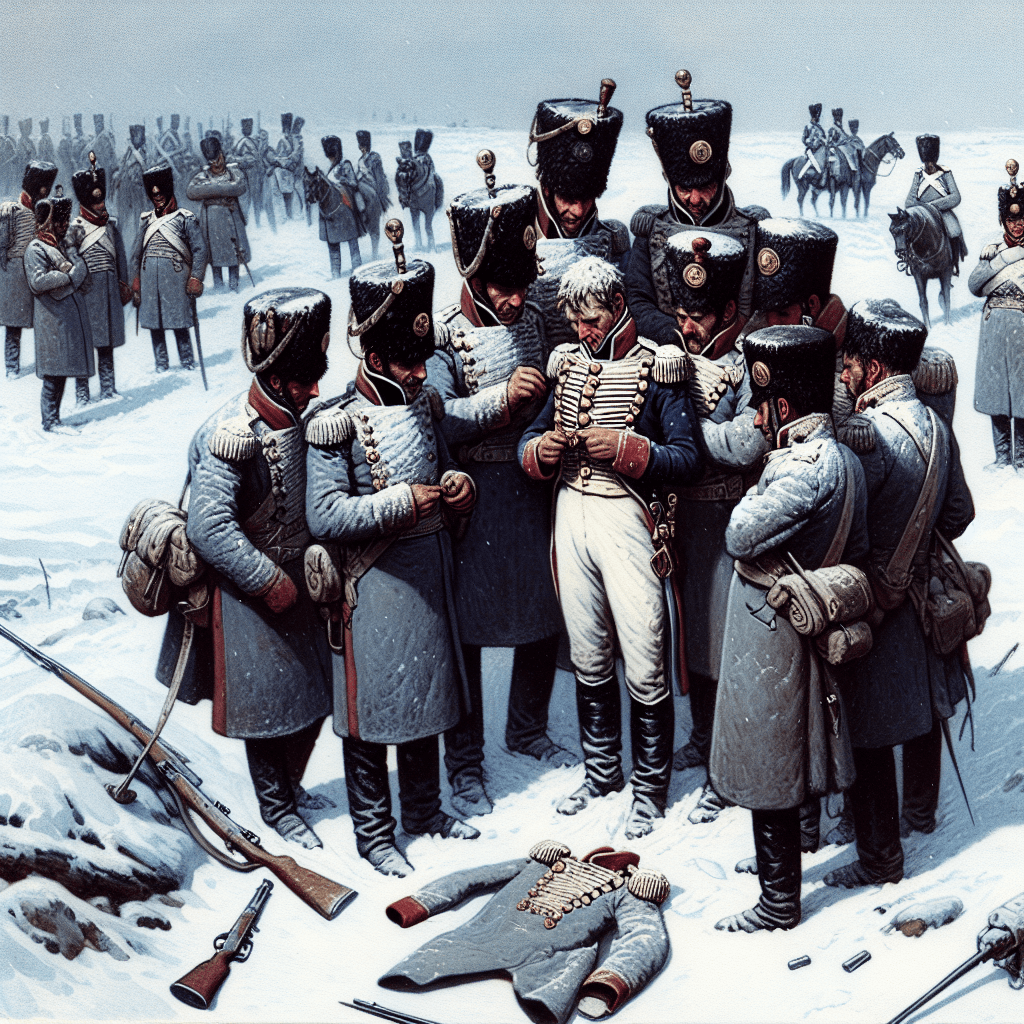

The catastrophic retreat of Napoleon's Grande Armée from Moscow in 1812 is a haunting chapter in military history. Of the over 600,000 soldiers who marched into Russia, fewer than 100,000 staggered out. While factors like starvation, disease, and relentless Cossack attacks were the primary killers, a fascinating and persistent theory points to a much smaller culprit: the humble buttons on the soldiers' uniforms. The story goes that as the temperatures plunged, these buttons disintegrated into dust, leaving the men unable to fasten their coats against the lethal cold. This post will delve into the science behind this claim, known as "tin pest," and examine whether this chemical curiosity was truly a contributing factor to one of history's greatest military disasters.

The Science Behind the Crumbling Buttons: What is Tin Pest?

To understand the button theory, we first need to understand the peculiar nature of the element tin. Tin exists in different structural forms, known as allotropes. The one we are most familiar with is:

- Beta-tin (β-tin): This is the shiny, silvery, and stable metallic form of tin used in everyday objects.

However, when the temperature drops below 13.2°C (55.8°F), beta-tin can begin a slow transformation into its other form:

- Alpha-tin (α-tin): This is a brittle, non-metallic, gray powder with a different crystal structure.

This transformation is called tin pest or tin disease. The process is slow at cool temperatures but accelerates dramatically in deep-freezing conditions, like those faced by Napoleon's army where temperatures fell below -30°C. The change is autocatalytic, meaning that once a spot of alpha-tin forms, it spreads like an infection throughout the metal, causing the entire object to crumble into a useless powder. An object afflicted with tin pest looks as if it is breaking out in gray sores before it completely disintegrates.

The Button Theory: A Plausible Culprit?

The theory connecting tin pest to Napoleon's defeat is compellingly simple. It posits that the soldiers of the Grande Armée were issued uniforms held together by buttons made of pure tin. As "General Winter" unleashed its full fury during the long retreat, these buttons would have been exposed to temperatures far below the critical threshold.

According to this hypothesis, the beta-tin buttons would have begun their transformation into powdery alpha-tin. Fasteners on greatcoats, trousers, and tunics would have crumbled, leaving soldiers unable to secure their clothing against the wind and snow. This catastrophic wardrobe malfunction would have drastically increased their vulnerability to frostbite and hypothermia, significantly contributing to the staggering death toll. It paints a vivid picture of a mighty army being undone not just by the enemy, but by the very laws of chemistry.

Fact or Folklore? Examining the Historical Evidence

While the science of tin pest is undeniable, its role in the 1812 campaign is heavily debated by historians and is now widely considered a myth. The case against the theory rests on several key points.

First, and most importantly, is the material of the buttons themselves. Archaeological evidence and historical records show that the vast majority of uniform buttons for the French infantry were not made of pure tin. They were typically crafted from more durable and cheaper materials like brass, bone, or pewter (an alloy of tin hardened with lead or antimony, which is far more resistant to tin pest). Pure tin was more expensive and generally reserved for the uniforms of high-ranking officers, who were better equipped to survive the retreat.

Second, archaeological digs at battle sites and mass graves from the 1812 campaign have unearthed thousands of uniform buttons. The overwhelming majority of these recovered artifacts are brass and have survived perfectly intact. Very few, if any, have shown evidence of disintegration due to tin pest.

Finally, there are no known firsthand accounts of the disaster. In the numerous diaries, letters, and memoirs written by the survivors of the campaign, they describe their suffering in harrowing detail—hunger, typhus, exhaustion, and frostbite are mentioned constantly. However, not a single soldier or officer wrote about their buttons mysteriously turning to dust. This is a crucial omission for a problem that would have been so widespread and deadly.

Conclusion

The story of Napoleon's army being defeated by crumbling tin buttons is a powerful and enduring legend. It serves as a fantastic real-world example for chemistry students and provides a neat, tangible explanation for a complex historical tragedy. However, the historical and archaeological evidence strongly suggests it is little more than a captivating myth. While tin pest is a real phenomenon, it did not play a significant role in the decimation of the Grande Armée. The true culprits were the grim, conventional realities of 19th-century warfare: failed logistics, rampant disease, brutal starvation, and the unforgiving Russian winter itself. The button theory reminds us that history is often more complicated than a single, simple explanation allows.