Why did New Englanders once dig up their dead to stop them from being vampires

When a mysterious plague known as "consumption" decimated their towns, 19th-century New Englanders turned to a horrifying solution: unearthing their own kin to kill the vampire they believed was responsible.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: A folk belief blamed the spread of tuberculosis on deceased family members draining the life from their living relatives. To stop this supposed vampire, New Englanders would exhume the body, burn the heart, and sometimes feed the ashes to the sick as a cure.

Beyond the Grave: Why Did New Englanders Once Dig Up Their Dead to Stop Them From Being Vampires?

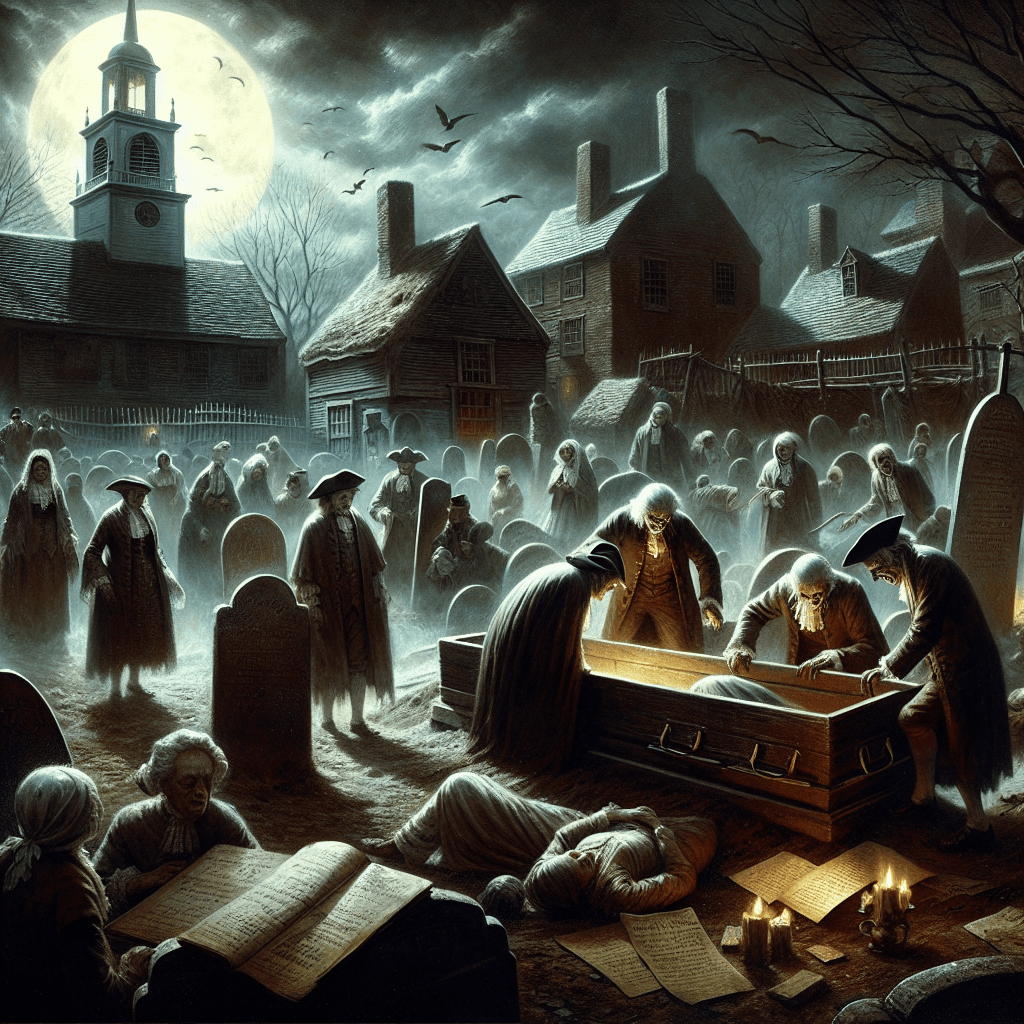

Long before the glittering vampires of modern fiction, a much grimmer figure haunted the towns and farms of 19th-century New England. This was not a caped aristocrat but a neighbor, a family member, recently deceased yet believed to be rising from the grave to prey on the living. In a bizarre and terrifying chapter of American history known as the "New England Vampire Panic," communities resorted to a desperate measure: digging up their dead. This practice wasn't born from a love of gothic horror but from a profound misunderstanding of a deadly disease. This post will uncover the real reason behind these grisly exhumations, revealing a story of fear, folklore, and the desperate search for a cure in a pre-scientific world.

The Shadow of Consumption: The Real Killer

The true villain of this story was not a supernatural entity but a relentless and poorly understood disease: tuberculosis. Known then as "consumption," the disease was a leading cause of death in the 18th and 19th centuries. Its symptoms were terrifyingly similar to the descriptions of a vampire's victim. Sufferers would:

- Grow pale and gaunt, seemingly "wasting away."

- Develop a persistent, rattling cough, often spitting up blood.

- Experience fevers and a slow, agonizing decline in health.

Because tuberculosis is highly contagious and often spreads through close family contact, it created a devastating pattern. One family member would fall ill and die, and soon after, another would begin showing the same symptoms, then another. To terrified onlookers, it appeared as though the first to die was somehow draining the life force from their surviving relatives from beyond the grave.

A Folkloric Diagnosis for a Medical Mystery

Without the knowledge of germ theory, people turned to the only explanation they had: folklore. The belief that the dead could harm the living was a superstition carried over from Europe. The New England "vampire," however, was different from its Eastern European cousin. It wasn't believed to be a creature that rose nightly to bite necks. Instead, the belief was that the deceased was a malevolent spirit, remaining in its grave but extending an unseen influence to drain the vitality of its living family members.

When a family was afflicted by consumption, suspicion would fall on the first member to have died from the disease. It was reasoned that this individual must be the "vampire" responsible for the ongoing sickness. This folkloric diagnosis offered both an explanation for the inexplicable and, more importantly, a tangible course of action to stop the plague.

The Desperate Ritual: How to "Kill" a Vampire

When fear and desperation reached a breaking point, the community would resort to exhumation. Led by the afflicted family, a group would dig up the corpse of the suspected vampire to search for signs of unnatural life. What they found often confirmed their worst fears.

A body buried for some time might appear bloated from gases, have long-looking hair and fingernails due to skin recession, and still have liquid blood in the heart and organs. To the untrained eye, these normal signs of decomposition looked like evidence that the corpse was still "fresh" and feeding.

Once the vampire was identified, a ritual was performed to destroy it. The most common practice involved removing the heart (and sometimes other organs) from the corpse and burning it to ash. In a final, desperate act, these ashes were often mixed with water and given to the sick family members as a medicinal tonic, in the hope it would break the curse and restore their health.

The most famous and well-documented case is that of Mercy Brown in Exeter, Rhode Island, in 1892. When her brother Edwin fell ill after several other family members had died of consumption, their father was persuaded to exhume Mercy's body. Finding what they believed was fresh blood in her heart, they burned it and fed the ashes to Edwin. The "cure" failed; he died two months later.

Conclusion

The New England vampire panic was a tragic confluence of disease, fear, and folk belief. The exhumations and rituals were not acts of malice but the desperate measures of people facing an invisible and terrifying killer. They used the logic available to them to explain a pattern of death that science had not yet unraveled. This historical episode serves as a powerful reminder of how societies respond to public health crises in the absence of scientific understanding. While we now have medical treatments for tuberculosis, the haunting story of Mercy Brown and others remains a testament to the dark power of fear and the lengths people will go to protect their loved ones.