Why did Victorians sometimes wear live glowing beetles as jewelry

Long before electric lights, the most dazzling accessory in a Victorian ballroom wasn't a diamond, but a live beetle worn as a shimmering, crawling brooch.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Victorians, fascinated by natural history and exotic novelties, wore live glowing beetles as a bizarre fashion statement. Their natural bioluminescence created a stunning, eye-catching effect in dimly lit ballrooms before the common use of electricity.

The Living Jewels of the Past: Why Did Victorians Sometimes Wear Live Glowing Beetles as Jewelry?

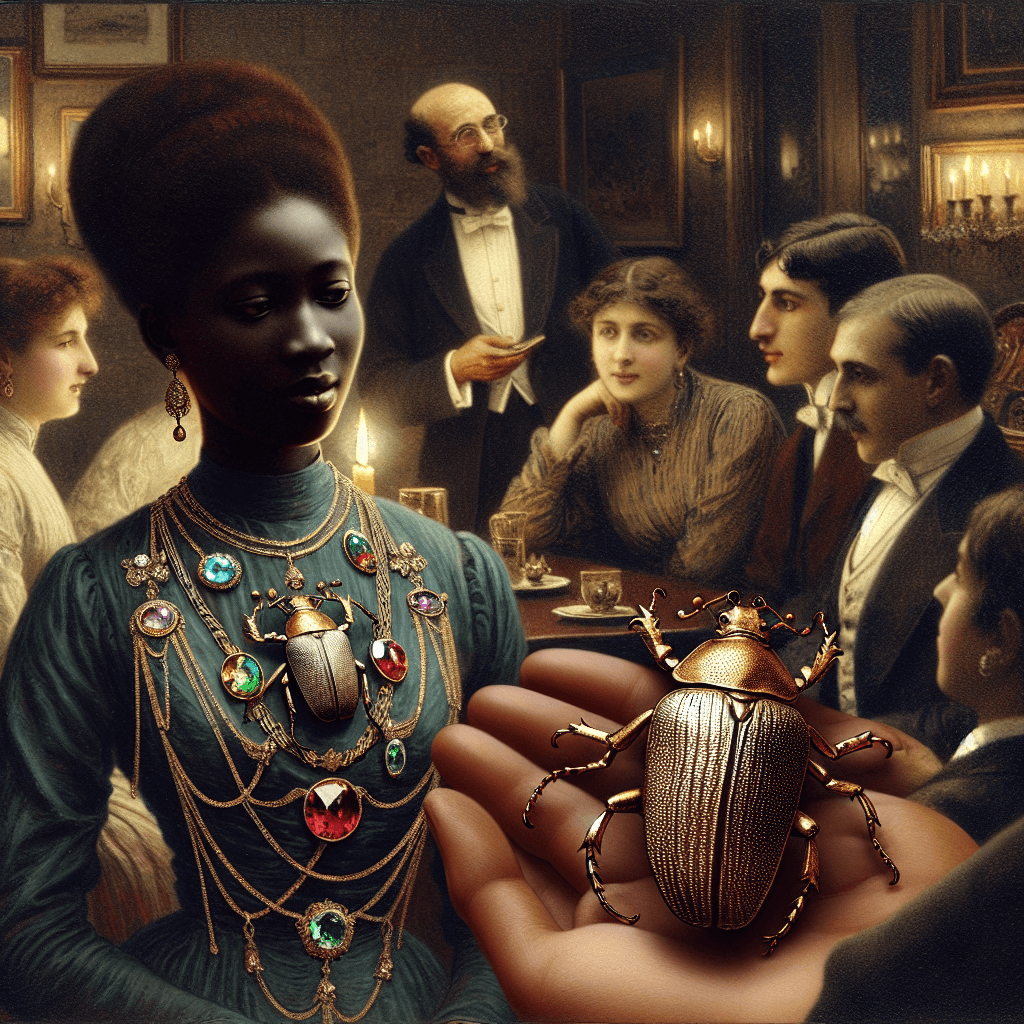

Imagine a grand Victorian ballroom, the air thick with the scent of perfume and wax candles, the scene illuminated by the soft, flickering glow of gaslight. Ladies in elaborate gowns adorned with pearls and diamonds glide across the floor. But look closer at one woman's hair or the lace on her dress—a soft, steady green light emanates, not from a gemstone, but from a living, breathing creature. This wasn't a scene from a fantasy novel; it was a genuine, albeit bizarre, fashion trend. This post explores the fascinating question: why did Victorians sometimes wear live glowing beetles as jewelry?

The Allure of the Cucujo Beetle

The insect at the center of this peculiar trend was not just any beetle. It was a specific species of bioluminescent click beetle, primarily Pyrophorus noctilucus, native to the tropical regions of the Americas. Known colloquially as the "cucujo" or "fire beetle," this remarkable insect possesses two spots on its thorax that emit a powerful, continuous greenish light, far brighter and more sustained than the intermittent flash of a common firefly.

To transform these living lights into accessories, Victorian women and their jewelers developed delicate methods:

- The beetles were carefully tethered with tiny, ornate gold chains.

- They were often attached to fine pins that could be fastened to a dress, a fan, or styled into the hair.

- To keep their insect-jewels alive and glowing brightly through an evening's event, owners would feed them small bits of sugarcane.

This practice, while short-lived and confined to the most fashion-forward circles, perfectly captured the spirit of the age.

A Fascination with Nature and the Exotic

The Victorian era (1837-1901) was a period of unprecedented scientific discovery and global exploration. The rise of natural history as a popular hobby meant that collecting ferns, butterflies, and shells was a respectable pastime for the middle and upper classes. This "natural history craze" was more than a hobby; it was a way to engage with the wonders of a world that was rapidly being mapped and cataloged by empires.

The cucujo beetle was the ultimate exotic import. Brought back from the West Indies and Mexico, it was a tangible piece of a faraway, tropical land. To wear one was to display not only wealth but also worldliness and a connection to the vast, mysterious corners of the British Empire. It was a living souvenir from the "New World," a conversation starter that blended scientific curiosity with imperial prestige.

Novelty, Spectacle, and a New Kind of Light

Victorian high society was fiercely competitive, and fashion was a key battleground. In a world of elaborate dresses and dazzling gemstones, the ultimate goal was to be unique. What could be more novel than a piece of jewelry that was alive and generated its own light? A glowing beetle was a guaranteed showstopper, a piece of natural magic that outshone even the most expensive diamond.

This trend also tapped into the era's fascination with new forms of illumination. As cities began to glow with gaslight and scientists experimented with the first forms of electricity, the natural, "cold light" of bioluminescence was a source of wonder. It represented a perfect fusion of nature and spectacle. Furthermore, while it seems cruel by modern standards, some historians note that wearing a living insect may have been perceived by some as a more "natural" or even "humane" alternative to the widespread practice of wearing taxidermied hummingbirds and other dead animals as accessories—a fashion choice that drew considerable criticism even at the time.

Conclusion: A Glimpse into the Victorian Mindset

The trend of wearing live glowing beetles as jewelry was more than just a fleeting, eccentric fad. It was a perfect reflection of the Victorian era's core fascinations: the obsession with natural history, the romance of exotic lands made accessible through empire, and an insatiable desire for novelty and spectacle. These living jewels offered a unique way to showcase status, intellect, and a connection to the natural world's most dazzling wonders. While the practice has long since vanished, it remains a brilliant, glimmering window into the complex and often contradictory mindset of a bygone era, reminding us that fashion is often a powerful expression of a society's deepest curiosities and ambitions.