Why do characters in silent films often move so fast and jerkily

That iconic, sped-up motion wasn't an artistic choice, but a fascinating technical accident we've been misinterpreting for over a century.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Silent films were shot at a lower, inconsistent frame rate with hand-cranked cameras. Playing them back at today's faster, standard speed artificially speeds up the motion, creating that signature fast and jerky look.

Flicker and Flash: Why Do Characters in Silent Films Often Move So Fast and Jerkily?

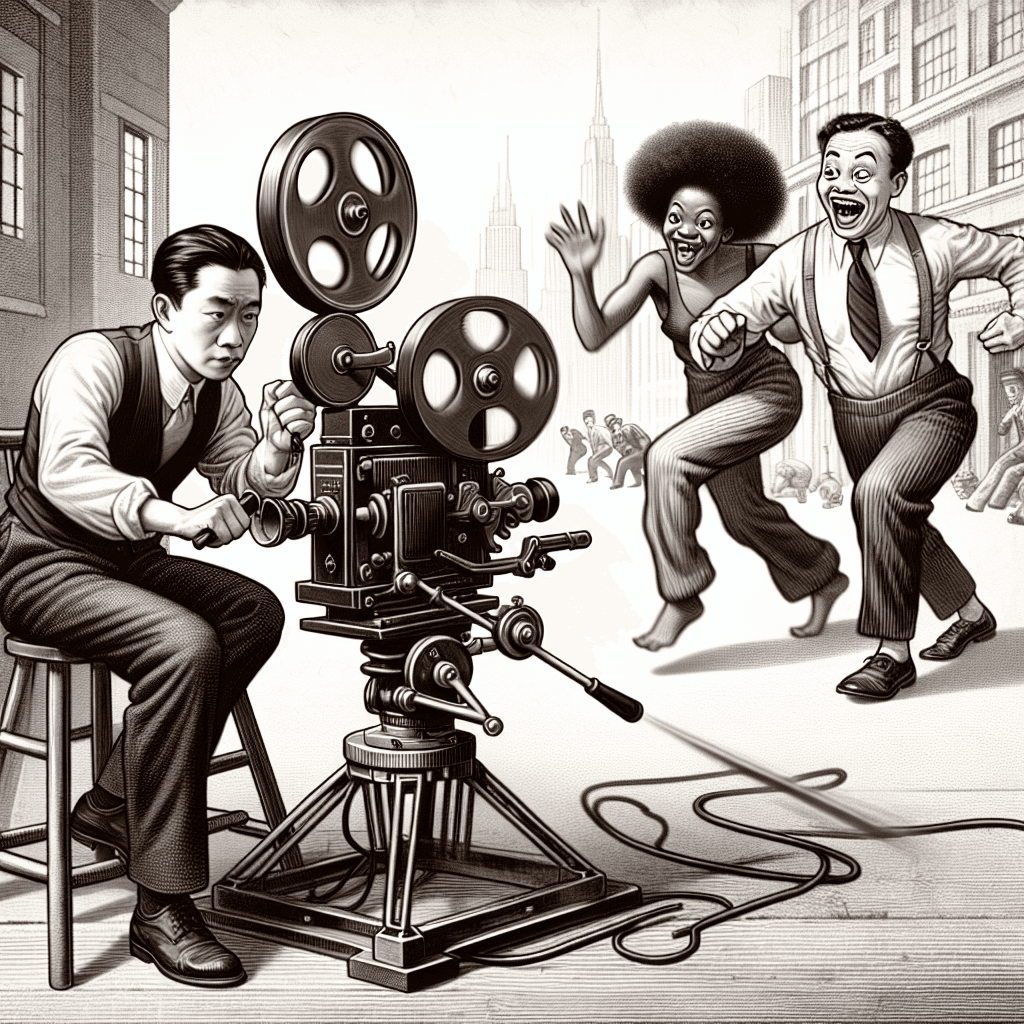

Picture a classic scene from the silent film era: Charlie Chaplin frantically waddling away from a pursuer, or the Keystone Kops tumbling over each other in a chaotic, high-speed chase. The motion is frantic, comical, and undeniably fast. For decades, this accelerated, jerky movement has defined our collective memory of silent cinema, leading many to believe it was a quirky stylistic choice of a bygone era. But what if this signature look isn't an artistic decision at all, but a fascinating accident of technology? This post will unravel the technical mystery behind the sped-up world of silent film, revealing a story of mismatched speeds and lost context.

The Core of the Issue: A Frame Rate Mismatch

The primary reason for the fast, jerky motion we associate with silent films is a simple technical conflict between how they were filmed and how they are now projected. It all comes down to a concept known as frames per second (fps).

- Modern Standard: Today, sound films are shot and projected at a global standard of 24 frames per second. This speed is fast enough to create the illusion of smooth, continuous motion and accommodate an optical soundtrack on the film strip.

- The Silent Era Standard (or Lack Thereof): In the early 20th century, there was no industry-wide standard. Cameras were hand-cranked, and the filming speed was determined by the cameraman. The typical rate hovered somewhere between 16 and 22 fps.

When a film shot at 16 fps is played on a modern projector running at 24 fps, the action is accelerated by 50%. Every second of film contains fewer frames than the projector is showing per second, forcing the projector to cycle through them faster to fill the time. This projection mismatch is the single biggest contributor to the "fast and jerky" effect.

The Art and Inconsistency of the Hand-Crank

Adding to the effect was the very human element of the hand-cranked camera. The cameraman wasn't just a passive operator; they were an active participant in creating the film's rhythm.

A skilled cinematographer would subtly alter their cranking speed to match the mood of a scene. For a dramatic or romantic moment, they might crank slightly slower (e.g., 18-20 fps) to create a more graceful, gentle pace when projected. For a chase or a comedic fight, they might crank faster (e.g., 22-24 fps) to capture more frames, which would then create a slow-motion effect when projected at the correct, slower speed.

This artistic variation, however, is lost when the film is played back at a locked, constant 24 fps. The subtle, human-driven changes in pace are flattened out, contributing to the unnatural and sometimes jerky feel of the on-screen movement.

Was It Ever Intentional?

It's a common myth that the fast motion was always a deliberate choice for comedic effect. While filmmakers certainly understood the tools at their disposal, the universal speed-up we see today is largely unintentional.

Pioneering comedy producer Mack Sennett was famous for undercranking—intentionally filming at a slower-than-normal speed (say, 12 fps) so that when projected at the era's standard of 16 fps, the action would look comically sped up. This was a specific, calculated effect. However, it doesn't account for why everything, from dramatic scenes to simple walking, often looks accelerated in modern viewings.

The original audiences would have seen these films projected at a speed much closer to how they were shot. Often, the projectionist also used a hand-cranked projector and would adjust the speed to match the on-screen action, ensuring a more naturalistic viewing experience that is almost entirely lost today in un-restored prints.

Restoring the Natural Pace

Thankfully, modern film preservationists are well aware of this issue. During digital restoration, technicians can meticulously analyze the film to determine its original, intended frame rate. They can then adjust the playback speed so that the final product—whether on a Blu-ray or a streaming service—reflects the natural, fluid motion that audiences would have seen a century ago. Watching a properly restored silent film can be a revelation, showcasing the grace of performers like Lillian Gish or the athletic precision of Buster Keaton as they were meant to be seen.

Conclusion

The iconic sped-up look of silent cinema isn't a primitive artistic quirk but a technical artifact of progress. The discrepancy between the variable, slower hand-cranked filming speeds of the silent era and the rigid, faster projection standards of the sound era is the true culprit. Understanding this changes our perception of these early cinematic works, allowing us to see past the jerky motion and appreciate them not as historical novelties, but as sophisticated works of art with a deliberate and natural pace. The next time you watch a silent film, try to find a restored version; you’ll be amazed at how a simple change in speed can bring a century-old performance to life in a whole new way.