Why do some modern cities hide entire ancient cities buried beneath them

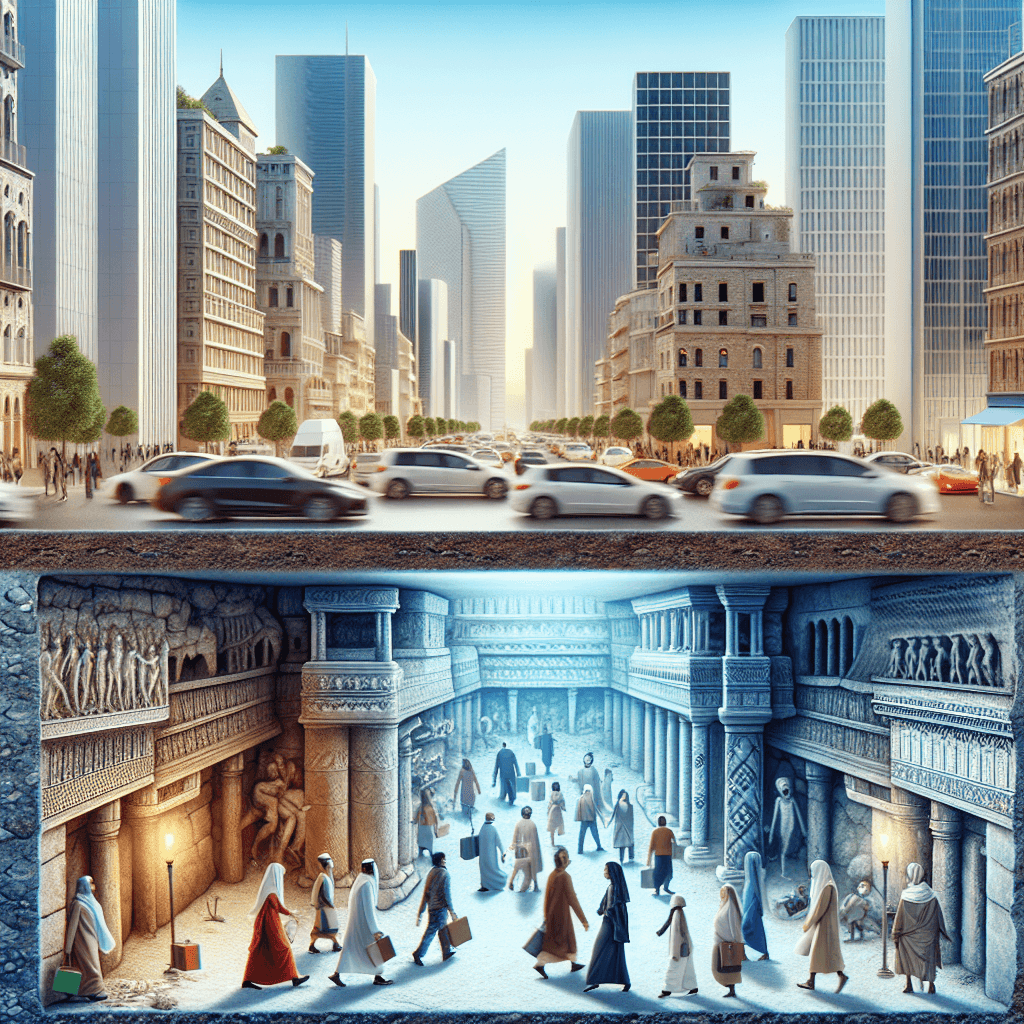

Beneath the bustling streets you walk every day isn't just soil and pipes—it's often another city entirely, a silent world waiting to be rediscovered.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Over centuries, people rebuilt cities in the same desirable locations. Instead of clearing old ruins and trash, they built directly on top, which, combined with natural soil and debris accumulation, gradually raised the ground level and buried the older layers.

Buried Histories: Why Do Some Modern Cities Hide Entire Ancient Cities Beneath Them?

Imagine you're on a construction crew in Rome, digging the foundation for a new building. Your shovel strikes something hard—not rock, but the perfectly cut stone of a 2,000-year-old Roman wall. This isn't a scene from a movie; it's a reality in many of the world's oldest urban centers. From London to Mexico City, a surprising number of modern metropolises are built directly on top of their ancient predecessors, creating a layer cake of history beneath the pavement. But why didn't people just move and start fresh? This post will explore the fascinating combination of natural forces, human habits, and strategic thinking that causes entire ancient cities to become buried beneath their modern counterparts.

The Slow, Unintentional Burial

The primary reason cities become buried is a gradual, centuries-long process of accumulation. It’s not a single cataclysmic event but a slow layering of debris, dirt, and daily life. This happens through a combination of human activity and natural processes.

The Cycle of Rebuilding

In the ancient world, when a building made of mud-brick, wood, or stone collapsed or was destroyed by fire or war, there was no fleet of bulldozers to haul away the rubble. The most practical solution was to simply level the debris, pack it down, and use it as a foundation for the next structure. Each time this happened—over and over for hundreds or thousands of years—the ground level of the entire settlement would rise. Archaeologists refer to the mounds created by this process in the Middle East as "tells." This cycle of destruction and reconstruction is the single largest contributor to the burial of ancient cities.

Everyday Life and Waste

Before modern sanitation and waste collection, trash was often tossed into the streets. This refuse—including food scraps, broken pottery, animal bones, and ash from fires—accumulated over time. Combined with mud washing down from buildings and wind-blown dust, this organic and inorganic waste slowly but surely raised street levels. What was once the ground floor of a building eventually became a basement, and what was a basement became completely subterranean.

Why Stay in the Same Spot? The Power of Location

If the old city was in ruins, why didn't people simply relocate and build a new city elsewhere? The answer lies in geography. The reasons a location was excellent for a city 2,000 years ago often remain the same reasons it's a great location today.

Founders of ancient cities were masters of strategic placement, choosing sites with crucial advantages that encouraged continuous settlement:

- Access to Water: A reliable water source is non-negotiable for a large population. Cities like London on the River Thames, Paris on the Seine, and Rome on the Tiber were founded on major rivers that provided drinking water, transportation, and trade.

- Defensible Terrain: Many cities were established on hills, at river bends, or in other naturally defensible positions that made them easier to protect from invaders.

- Trade and Resources: A prime location at the crossroads of major trade routes or near valuable natural resources ensured economic prosperity, making the site too valuable to abandon.

The immense investment in infrastructure—even in ruins—and the established importance of the site as a center of commerce, religion, or power created a powerful incentive to stay and rebuild rather than start over from scratch in an unknown location.

Unearthing the Past: Modern Examples

This historical layering is evident all over the world. In Mexico City, the ruins of the Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, lie directly beneath the modern city center. The Templo Mayor, a massive Aztec temple, was excavated right next to the city's main cathedral, a powerful visual of one civilization being built directly atop another.

In London, construction for new office buildings frequently uncovers remnants of the Roman city of Londinium. A famous example is the Roman Temple of Mithras, discovered in 1954 and now beautifully displayed in the basement of the Bloomberg European headquarters. Similarly, building new subway lines in Rome is a notoriously slow process because digging almost anywhere in the city center becomes an archaeological excavation, revealing everything from ancient villas to imperial forums several meters below the current street level.

Conclusion

The cities buried beneath our feet are not lost through a single act of nature but are preserved by the very processes of life, decay, and rebirth that define urban history. A combination of slow, steady accumulation from waste and rebuilding, coupled with the enduring strategic value of a city's location, creates a vertical timeline of civilization. The next time you walk through an ancient city like Athens or Istanbul, remember that the streets you tread are just the latest chapter in a story that extends deep into the earth—a hidden metropolis of history, waiting just beneath the surface.