Why do some underwater insect larvae build intricate suits of armor from sand and jewels

Beneath the surface of creeks and rivers, tiny architects are building wearable mosaics of sand and gemstones not for beauty, but for brutal, life-or-death survival.

Too Long; Didn't Read

Caddisfly larvae build intricate cases from surrounding debris for protection from predators, for camouflage, and to weigh themselves down in strong currents so they don't wash away.

Nature's Jewelers: Why Do Some Underwater Insect Larvae Build Intricate Suits of Armor from Sand and Jewels?

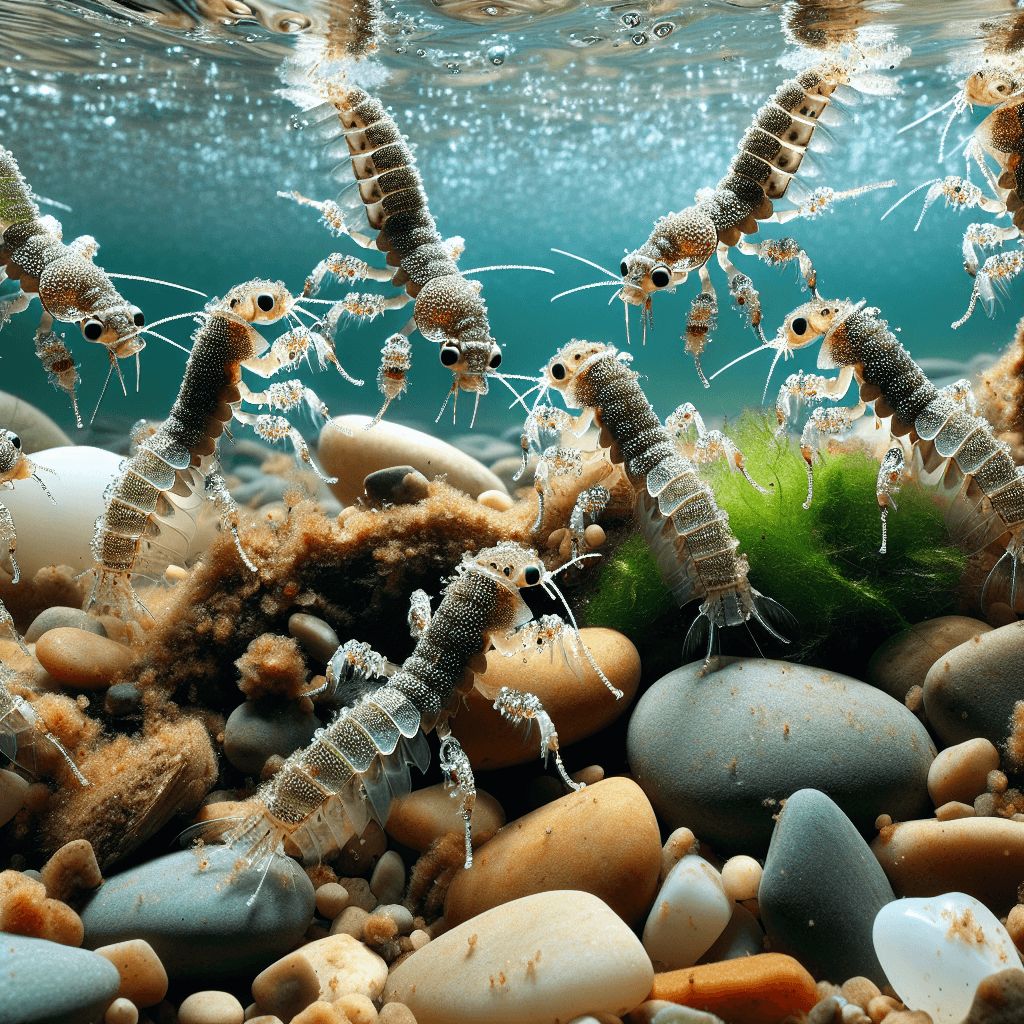

Imagine an artist meticulously selecting tiny pebbles, sand grains, and even glittering fragments to construct a protective mosaic. Now, imagine this artist is not human but a tiny insect living at the bottom of a stream. This is the remarkable reality for the larvae of the caddisfly, nature’s most fascinating underwater architects. These creatures build elaborate, mobile homes—or suits of armor—from materials found in their environment. But this isn't simply for show. This behavior is a masterclass in survival, driven by millions of years of evolution. This post will delve into the fascinating world of these insect engineers to uncover why they build these intricate cases.

Meet the Underwater Architects: The Caddisfly Larva

The creators of these stunning structures are the aquatic larvae of caddisflies, an order of insects known as Trichoptera. While the winged adults live on land, caddisflies spend the majority of their lives—from months to several years—as larvae in freshwater rivers, streams, and lakes.

To build their protective cases, the larva secretes a strong, adhesive silk from its salivary glands. This natural cement is used to bind together a variety of materials, including:

- Sand grains and tiny pebbles

- Snail shells

- Twigs and leaf fragments

- Other organic debris

The larva carefully selects and positions each piece, slowly building a tubular case around its soft, vulnerable body, leaving only its head and legs exposed to move and feed.

A Fortress of Function: The Reasons Behind the Armor

The caddisfly larva’s case is far more than a simple shelter; it is a multi-functional tool essential for survival. The primary reasons for this incredible feat of engineering are protection, stability, camouflage, and even respiration.

Protection from Predators

The most critical function of the case is defense. The larva's soft abdomen is a prime target for predators like fish (especially trout), stonefly nymphs, and dragonfly larvae. The hard, gritty case acts as a physical shield, making the larva difficult to attack and swallow. The rough texture can deter fish, who may spit out the larva after an attempted bite. This armor allows the caddisfly to graze on algae and debris with a much lower risk of becoming a meal itself.

Camouflage and Disguise

By using materials from its immediate surroundings, the caddisfly larva creates the ultimate camouflage. A case built from the sand and pebbles of a specific streambed makes the larva virtually invisible to predators relying on sight. This form of disguise, known as crypsis, allows it to blend seamlessly into the background, hiding in plain sight from would-be attackers.

Ballast in Flowing Water

Life in a fast-moving stream is perilous. The constant current threatens to sweep small creatures away. To combat this, many caddisfly species intentionally use heavier materials like dense sand grains and small stones. This added weight acts as ballast, helping to anchor the larva to the streambed. This prevents it from being dislodged and washed downstream, allowing it to thrive in environments where other insects might struggle.

Aiding Respiration

Perhaps the most surprising function is the case's role in breathing. Caddisfly larvae breathe through gills located along their abdomen. To get enough oxygen, they need a constant flow of fresh water over these gills. By rhythmically undulating its body inside the tube-like case, the larva creates a current, actively pumping oxygen-rich water through its portable home. The case itself helps channel this flow, acting as a personal, highly efficient respiratory device.

From Sand Grains to Gemstones

While caddisflies in the wild use natural materials, their innate building instinct is so strong that they will use whatever is available. This has been famously demonstrated by artists, such as the French artist Hubert Duprat. In a controlled environment, Duprat provides caddisfly larvae with materials like gold flakes, pearls, and tiny fragments of turquoise and other precious gems. The insects, following their natural programming, meticulously construct their cases from these "jewels," creating stunning, wearable pieces of art. This experiment beautifully highlights that the building behavior is a deep-seated instinct, not a learned skill.

Conclusion

The intricate suit of armor built by a caddisfly larva is a testament to the elegance and efficiency of natural selection. What might look like a simple collection of debris is, in fact, a sophisticated, multi-purpose survival tool. It provides a shield from enemies, camouflage from prying eyes, stability against powerful currents, and a means to breathe in its underwater world. The next time you walk by a clear, flowing stream, take a moment to look closer. You might just spot one of nature’s most skilled jewelers, a tiny architect whose beautiful creation is the very key to its existence.