Why do spaghetti stains cling to plastic tubs but not glass bowls

Discover why tomato sauce permanently dyes your plastic containers but wipes clean from glass—it's not your scrubbing power, but a simple case of molecular attraction.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Plastic is porous and oil-based, just like the red pigment in tomato sauce, so they bond together and cause a stain. Glass is non-porous and has a different chemical structure, so the sauce has nothing to cling to and wipes off easily.

The Science Behind the Stain: Why Do Spaghetti Stains Cling to Plastic Tubs but Not Glass Bowls?

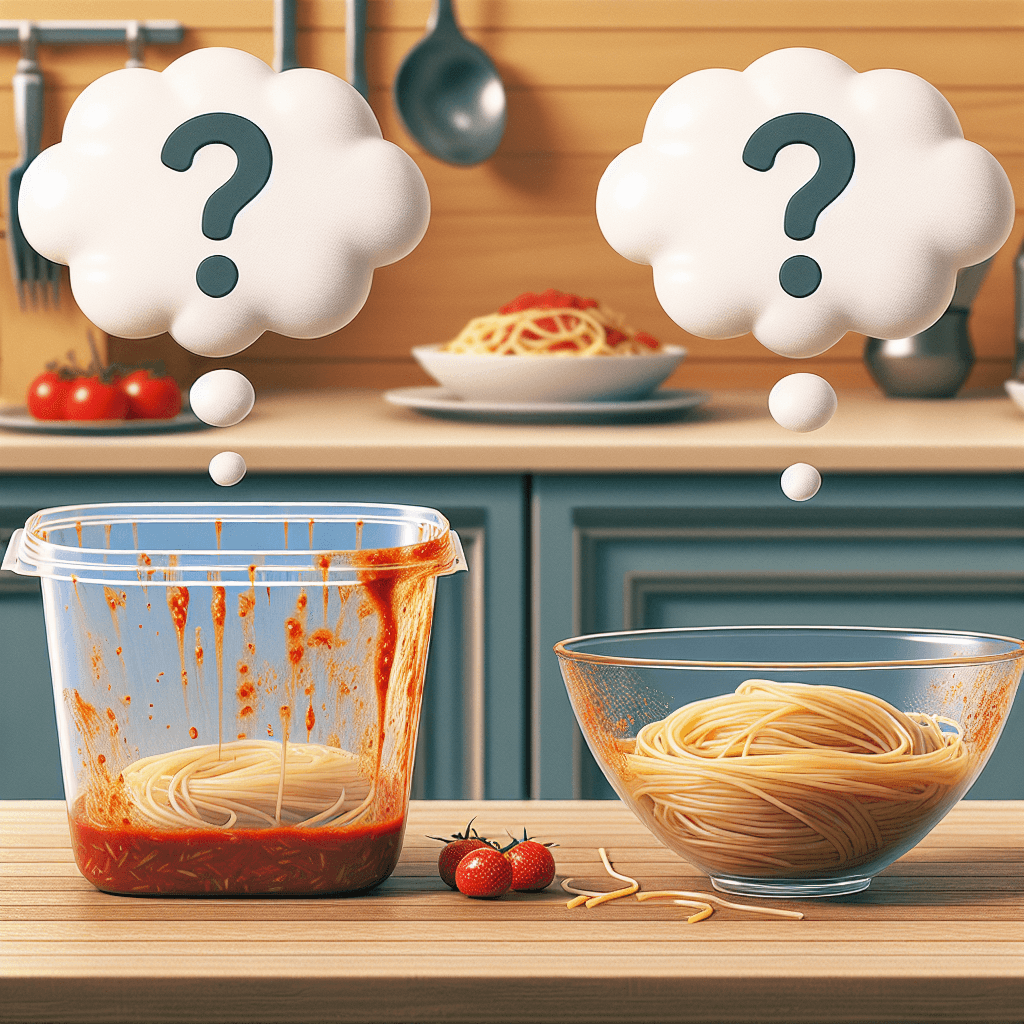

We’ve all been there. You open the dishwasher, expecting sparkling clean containers, only to find that your plastic tub still bears the ghostly orange shadow of last week's spaghetti bolognese. Yet, the glass bowl used for the very same meal is perfectly pristine. It’s a common kitchen frustration that feels like a mystery, but the answer isn’t magic—it’s chemistry. This stubborn stain phenomenon is a perfect illustration of how different materials interact on a molecular level.

This blog post will unravel the scientific reasons behind this culinary conundrum. We'll explore the properties of the key staining agent in tomato sauce, compare the molecular structures of plastic and glass, and explain exactly why one material is a magnet for stains while the other is effortlessly resistant.

The Science of the Stain: It's All About Lycopene

The primary culprit behind that infamous orange tint is a molecule called lycopene. Lycopene is a carotenoid, which is a natural pigment that gives many fruits and vegetables their vibrant red, orange, and yellow colors. In the case of spaghetti sauce, it's the lycopene in tomatoes that is responsible for both its rich red hue and its powerful staining ability.

The key chemical property of lycopene is that it is a nonpolar molecule. In chemistry, the principle of "like dissolves like" is fundamental. This means that nonpolar substances are attracted to and readily dissolve in other nonpolar substances. Lycopene is also lipophilic, which is a fancy way of saying it is "fat-loving" or "oil-loving." Since oils and fats are also nonpolar, lycopene dissolves easily into them, which is why the oils in your spaghetti sauce become a potent delivery vehicle for the stain.

Plastic vs. Glass: A Tale of Two Surfaces

Now that we've identified our staining agent, the mystery comes down to the nature of the containers themselves. Plastic and glass have fundamentally different molecular structures, which dictates how they interact with the nonpolar lycopene molecules.

Why Plastic is a Perfect Match for Stains

Most food storage containers are made from plastics like polypropylene. At a molecular level, plastic is a polymer, consisting of long chains of hydrocarbons. Just like the oils and lycopene in your tomato sauce, plastic is also nonpolar.

When you store or, even worse, microwave spaghetti sauce in a plastic container, a few things happen:

- Chemical Attraction: The nonpolar lycopene molecules in the sauce see the nonpolar plastic as a kindred spirit. They are chemically attracted to each other, creating a bond.

- Microscopic Porosity: On a microscopic scale, the surface of plastic is porous. It's filled with tiny gaps and crevices.

- Heat Expansion: When you heat the container in the microwave, the plastic expands. This causes those microscopic pores to open up even wider, inviting the oily, lycopene-rich sauce to seep deep into the material's structure.

As the plastic cools, its pores shrink, effectively trapping the red pigment molecules inside. No amount of scrubbing can reach these embedded stains, leaving behind that familiar and frustrating orange hue.

Why Glass Stays Spotless

Glass, on the other hand, is a completely different story. Glass is an amorphous solid with a molecular structure that is polar. Furthermore, its surface is incredibly smooth and non-porous.

Because of these properties, glass is the opposite of plastic when it comes to spaghetti sauce:

- Chemical Repulsion: The nonpolar lycopene molecules have no chemical affinity for the polar surface of the glass. There's no "like dissolves like" attraction happening here.

- Impermeable Surface: With no pores for the pigment to seep into, the sauce simply sits on top of the glass.

When you wash a glass bowl, the soap and water can easily lift the sauce and its staining pigments right off the smooth, non-porous surface, leaving it perfectly clear and clean.

Conclusion

The stubborn spaghetti stain on your plastic Tupperware isn't a sign of a faulty dishwasher or weak soap; it's a simple lesson in chemistry. The "like dissolves like" principle dictates that the nonpolar, oil-loving lycopene in tomato sauce will bond with and seep into the nonpolar, porous structure of plastic, especially when heated. In contrast, the smooth, non-porous, and polar surface of glass offers no purchase for the stain, allowing it to be washed away effortlessly.

Understanding this science not only solves a common kitchen mystery but also provides a practical solution. The next time you're packing up leftover pasta, reach for a glass container. You'll not only prevent the dreaded orange stain but also ensure your containers stay looking new for years to come.