Why do we involuntarily make a choppy ha-ha sound when we laugh

Ever wonder why a real belly laugh comes out as a choppy "ha-ha" instead of a smooth sound? The answer lies in an involuntary reflex that hijacks your diaphragm, and the reason is more surprising than you think.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Laughter is an involuntary reflex where your diaphragm and chest muscles spasm, forcing air out in choppy ha-ha bursts across your vocal cords. It's a primitive brain signal for social bonding and to show you are not a threat.

The Science of Laughter: Why Do We Involuntarily Make a Choppy "Ha-Ha" Sound When We Laugh?

Have you ever laughed so hard you couldn't breathe, your stomach ached, and tears streamed down your face? In that moment of pure, unbridled joy, did you ever stop to wonder why laughter sounds the way it does? It’s not a smooth, continuous sound like a hum or a sigh. Instead, it’s a series of sharp, choppy, and often loud vocal bursts: the classic "ha-ha-ha." This universal human sound is far from random; it's the result of a fascinating and complex physiological process that we have very little conscious control over. This post will explore the intricate mechanics behind our laughter, revealing why our bodies produce that distinct, staccato sound when we find something funny.

The Diaphragm's Spasmodic Dance

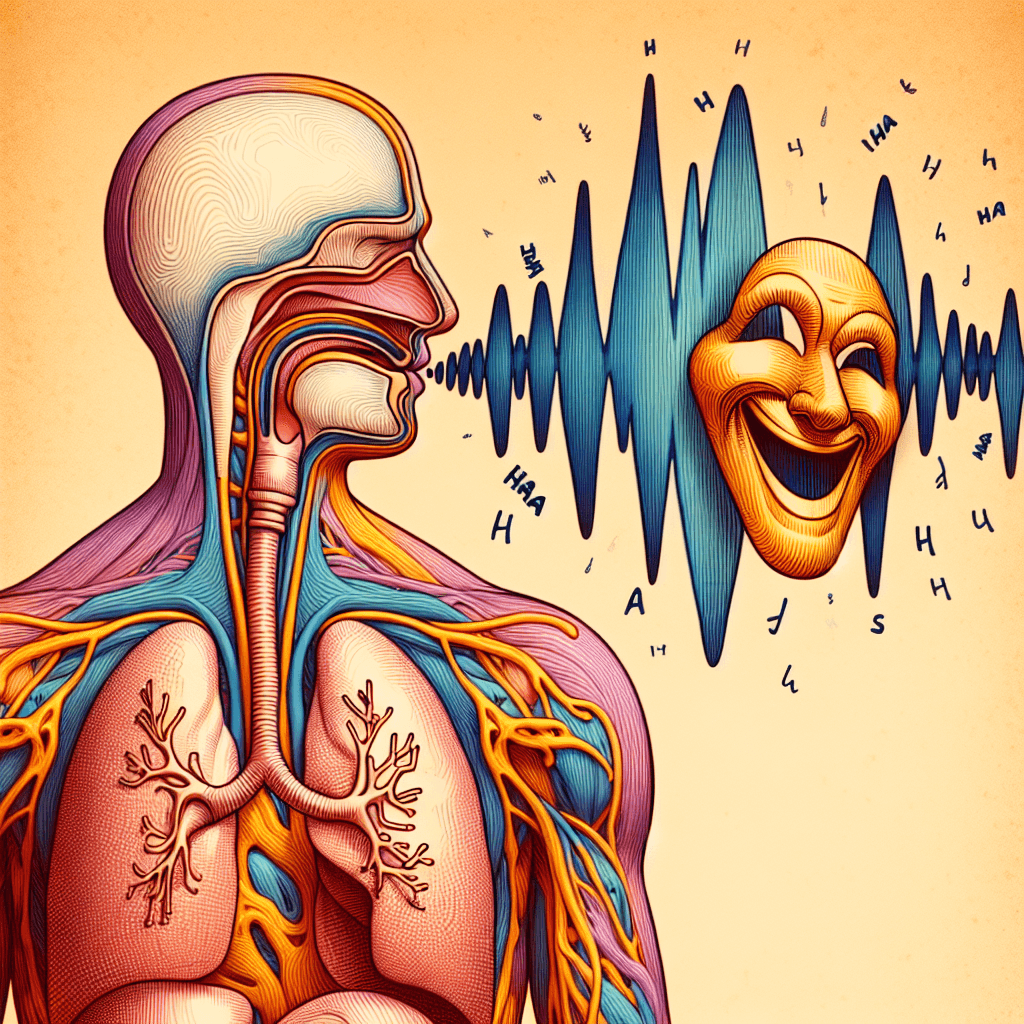

The root of the "ha-ha" sound lies not in our throat, but deep in our torso with a large, dome-shaped muscle: the diaphragm. The diaphragm is the primary muscle responsible for breathing, contracting to pull air into the lungs and relaxing to push it out. When you speak or sing, you exert precise, voluntary control over this process to regulate the flow of air.

Laughter, however, hijacks this system. When you experience a strong bout of laughter, your brain triggers the diaphragm and other respiratory muscles, like the intercostals between your ribs, to engage in a series of powerful, involuntary contractions or spasms.

- Each convulsion violently forces a burst of air out of your lungs.

- This process is rapid and repetitive, creating a choppy expulsion of air rather than a smooth, steady stream.

- It's this spasmodic action that causes the breathless feeling and muscle soreness we often feel after a particularly intense laugh.

Think of it as your respiratory system being put on a very fast, very bumpy rollercoaster that you can't get off until the ride is over.

How Vocal Cords Turn Air into Sound

As these powerful bursts of air are forced up from the lungs, they travel through your larynx, or voice box. Stretched across the larynx are your vocal cords, the tissues that vibrate to produce the sound of your voice.

During controlled speech, you modulate the tension in your vocal cords and the flow of air to create specific sounds. Laughter throws that precision out the window. According to neuroscientist Robert Provine, a pioneer in laughter research, each of the spasmodic air bursts from the diaphragm causes the vocal cords to vibrate, producing a single, short, vowel-like note. One "ha" is essentially one muscle spasm pushing one puff of air across the vocal cords.

Provine’s research found that these notes are typically repeated in quick succession, about every 210 milliseconds. This rapid-fire sequence of air bursts and vocal cord vibrations is what we perceive as the rhythmic, choppy sound of laughter.

An Involuntary Brain Reflex

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of laughter is that it's largely an involuntary reflex. While you can consciously decide to speak, you can't easily decide to produce a genuine, soul-shaking laugh. This is because the physical act of laughing is controlled by an evolutionarily ancient part of the brain—the brainstem—which governs fundamental functions like breathing and reflexes.

Speech, on the other hand, is managed by the motor cortex, a more modern part of the brain responsible for fine motor control. This is why you can't talk and genuinely laugh at the same time. The two systems are competing for control over the same anatomical parts (diaphragm, larynx, and vocal cords), and the more primitive, involuntary reflex of laughter usually wins. This involuntary nature is what makes laughter such an honest social signal; it's difficult to fake convincingly because the underlying physiological mechanism is not under our direct command.

Conclusion

The next time you find yourself in the throes of a hearty laugh, take a moment to appreciate the incredible biological performance taking place. That choppy "ha-ha-ha" sound is not just a noise; it’s the audible result of a complex chain reaction. It begins with an emotional trigger that causes your diaphragm and chest muscles to spasm, forcing air from your lungs in sharp bursts. These bursts then vibrate your vocal cords to create the staccato notes of joy we all recognize. This beautifully intricate and involuntary process serves as a powerful reminder of how deeply connected our emotions are to our physical bodies, turning a simple reflex into one of humanity's most important tools for social bonding.