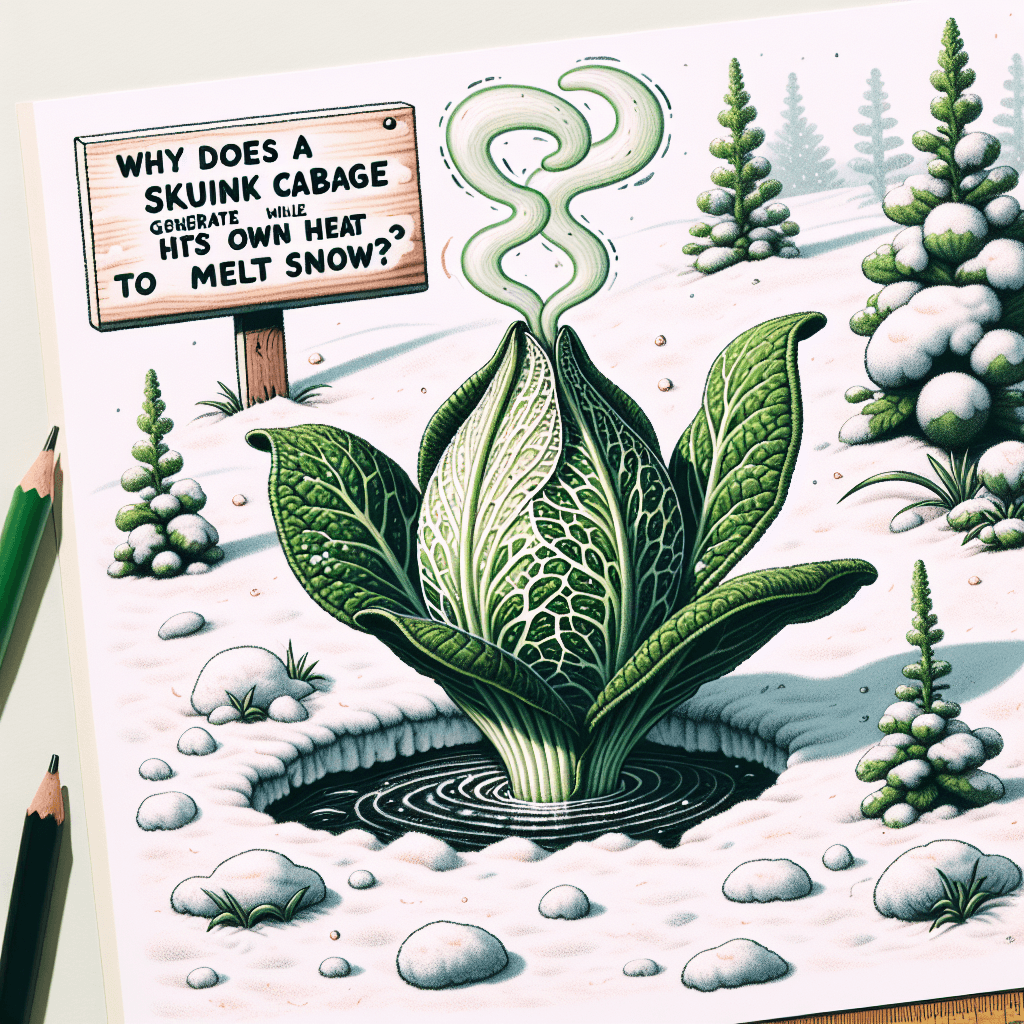

Why does a skunk cabbage generate its own heat to melt snow

This bizarre plant acts as its own tiny furnace, generating enough heat to melt through solid ice and bloom while winter still rages. Uncover the ingenious evolutionary advantage that powers this 'warm-blooded' wonder.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Skunk cabbage generates heat to melt snow for a head start on the growing season. This allows it to attract the first available pollinators with its warmth and foul scent, ensuring pollination without competition from other plants.

Nature's Furnace: Why Does a Skunk Cabbage Generate Its Own Heat to Melt Snow?

Imagine a late winter walk through a frozen wetland. The ground is still covered in a blanket of snow, and the air holds a biting chill. Yet, pushing up through the ice and snow is a bizarre, mottled purple-and-green hood. This is the Eastern skunk cabbage (Symplocarpus foetidus), a true pioneer of spring. But how does it defy the freezing temperatures? This remarkable plant possesses a rare biological superpower: it generates its own heat. This blog post will delve into the fascinating science behind this phenomenon, exploring exactly how the skunk cabbage creates its internal furnace and, more importantly, the clever evolutionary reasons why it melts its way into the world.

The Phenomenon of Thermogenesis: A Plant's Internal Furnace

The ability to produce heat is known as thermogenesis. While common in warm-blooded animals like us, it is exceedingly rare in the plant kingdom. The skunk cabbage is one of the best-known examples of a thermogenic plant. It can maintain the temperature inside its flowering structure (the spathe) at a cozy 15-35°C (60-95°F) warmer than the surrounding air, even when outdoor temperatures are below freezing.

But how does it do it? The heat generation occurs in the mitochondria, the powerhouses of its cells, located in the fleshy, flower-covered spike called the spadix. The plant uses a specialized metabolic pathway that is a modified form of cellular respiration. In typical respiration, energy from starches is efficiently converted into ATP, the cell's energy currency. The skunk cabbage, however, engages a sort of "metabolic shortcut." This alternate pathway is highly inefficient, causing a large amount of the energy stored in its roots to be released directly as heat instead of being captured in ATP. It essentially burns through its winter energy reserves to create a warm microclimate.

The Competitive Edge: Getting a Head Start on Spring

So, why go to all this metabolic trouble? The primary reason is to gain a significant competitive advantage. By generating heat, the skunk cabbage accomplishes several crucial goals for survival and reproduction:

- Early Emergence: Melting the snow and frozen ground allows the plant to emerge and flower weeks, or even months, before its competitors. This head start is critical on the forest floor.

- Beating the Canopy: It flowers and completes much of its reproductive cycle before the forest trees above leaf out. Once the canopy is full, very little sunlight reaches the ground, making it difficult for other plants to thrive. The skunk cabbage has already secured its spot and its sunlight.

- Securing Pollinators: In the cold, barren landscape of late winter, there are very few active insects. By being the first flower on the scene, the skunk cabbage has the undivided attention of the few pollinators that are around.

A Warm, Smelly Invitation: Attracting Early Pollinators

The skunk cabbage’s heat production is also intricately linked to its pollination strategy. The plant gets its name from the pungent, foul odor it emits, which many compare to rotting meat. While unpleasant to us, this scent is an irresistible invitation to its preferred pollinators: carrion-loving insects like flies and certain beetles.

The heat plays a vital role here. By warming the air within its hooded spathe, the plant helps to volatilize and disperse these odorous compounds, essentially sending out a powerful, long-distance signal to any early-emerging insects.

Furthermore, the warm, sheltered interior of the spathe acts as a cozy haven for these cold-blooded insects. A visiting fly not only gets a potential meal but also a warm place to rest and increase its own body temperature. As these insects move around inside the warm flower, they inadvertently transfer pollen, ensuring the skunk cabbage successfully reproduces. It’s a brilliant strategy: offering warmth and a familiar (if foul) scent to attract the only pollinators available.

Conclusion

The skunk cabbage's ability to generate its own heat is more than just a biological curiosity; it is a masterclass in evolutionary adaptation. By burning through its energy reserves to create warmth, it melts through the snow to claim the first spot in the spring lineup. This gives it a critical head start on its competitors and allows it to attract the specific, cold-hardy pollinators it needs to reproduce. It's a powerful reminder of the incredible and often hidden strategies that life uses to thrive in even the harshest conditions. So, the next time you are out on a late-winter hike, keep an eye out for this remarkable pioneer, a warm-blooded plant bravely melting its way toward spring.