That Awkward Moment: Why Does Your Own Voice Sound So Different on a Recording

Ever cringed at the sound of your own voice on a recording? It's a near-universal experience, and there's a clear scientific reason why the voice in your head doesn't match what you hear played back.

Too Long; Didn't Read

Your voice sounds different on a recording because you normally hear it through a combination of air and bone conduction. A recording only captures the air-conducted sound, which is how everyone else hears you.

That Awkward Moment: Why Does Your Own Voice Sound So Different on a Recording?

Ever listened back to a voicemail you left, a video you were in, or even just a quick voice note, and immediately cringed? "Is that really what I sound like?" It's a near-universal experience. That slightly higher-pitched, thinner, almost unfamiliar voice playing back rarely matches the resonant tones we hear inside our own heads. This isn't just vanity or self-consciousness; there's a clear scientific reason behind this auditory discrepancy. This post dives into the fascinating physics and physiology that explain why your recorded voice sounds so different from the one you perceive daily.

The Two Paths of Sound: How You Hear Yourself Speak

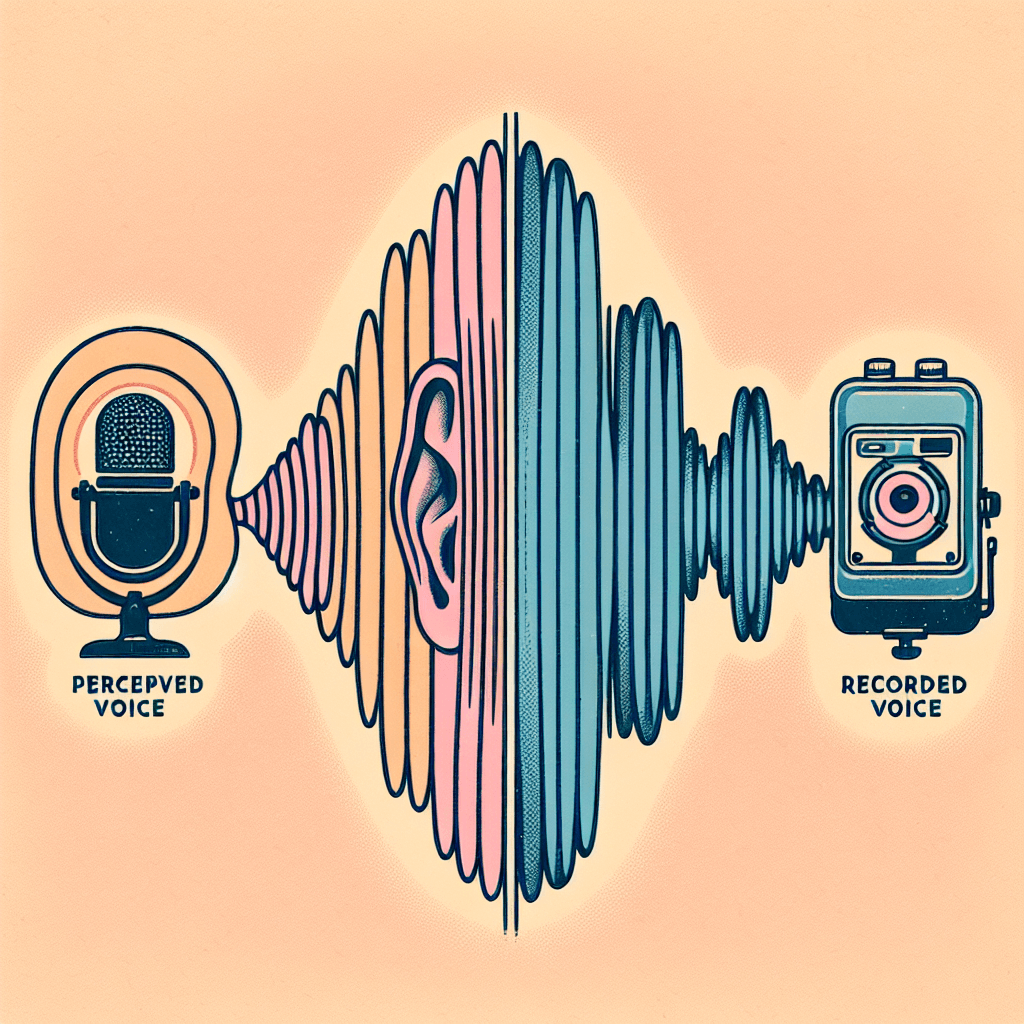

When you speak, you hear your voice through two distinct pathways simultaneously:

- Air Conduction: This is the standard way we hear external sounds. Sound waves produced by your vocal cords travel out of your mouth, through the air, and into your ear canal. These waves vibrate your eardrum, which transmits the vibrations through the tiny bones of the middle ear (ossicles) to the cochlea in the inner ear. The cochlea converts these vibrations into electrical signals that your brain interprets as sound. This is also how other people hear your voice.

- Bone Conduction: This is the internal route unique to hearing your own voice. As your vocal cords vibrate, they also cause vibrations throughout the bones and tissues of your skull, including those directly surrounding your inner ear. These vibrations travel directly through your bones to the cochlea, bypassing the eardrum and middle ear entirely.

The crucial difference lies in how bone conduction transmits sound. Your skull tissues are better at conducting lower-frequency vibrations than higher-frequency ones. This means bone conduction adds a layer of bass and resonance to the sound signals reaching your cochlea.

Therefore, the voice you hear inside your head is a composite sound – a blend of air-conducted sound and bone-conducted sound, with the latter adding depth and richness that isn't actually present in the sound waves travelling through the air.

The Recording Reality: Capturing Only Air Conduction

Now, consider what happens when you use a microphone and recording device. Microphones work much like our ears do for external sounds – they capture sound waves travelling through the air.

- No Bone Conduction: A microphone sits outside your body. It cannot pick up the internal vibrations travelling through your skull.

- Air Conduction Only: It records only the air-conducted sound waves produced by your voice – the same sound waves that reach the ears of anyone listening to you speak.

When you play back that recording, you are hearing your voice purely through air conduction, just like everyone else does. The lower-frequency richness added by bone conduction, which you are accustomed to hearing internally, is completely absent. This makes the recorded voice sound higher-pitched, thinner, and often quite different from your internal perception. Essentially, the recording presents the objective reality of your voice as perceived externally.

Why the Cringe? Expectation vs. Reality

Beyond the physics, there's a psychological element. We build our self-perception partly around the voice we hear internally. It's familiar, comfortable, and part of our identity. Hearing the recorded version confronts us with a sound that doesn't match our internal experience.

This discrepancy between expectation (the rich voice in our head) and reality (the air-conducted voice on the recording) can be jarring. It feels unfamiliar and "wrong" simply because it lacks the bone-conducted frequencies we automatically factor into our perception of our own voice. It's not necessarily that the recorded voice sounds bad, just that it sounds unexpectedly different.

Conclusion: Embracing Your Recorded Voice

So, the next time you hear your voice on a recording and feel that familiar twinge of surprise or discomfort, remember the science. The difference isn't in your head (well, not entirely!), but rather in the pathways sound takes to reach your inner ear. You normally perceive your voice through a combination of air and bone conduction, giving it a deeper quality only you can hear. Recordings, like other people, only capture the air-conducted sound. Understanding this physical process demystifies the phenomenon. While it might take some getting used to, the voice on that recording is, in fact, a more accurate representation of how the rest of the world hears you speak.