Why was a popular type of green wallpaper once a leading cause of death

It was the most coveted home decor trend of the 19th century, but this stunning green wallpaper was also a silent killer, slowly releasing deadly arsenic into the air of fashionable homes.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: Popular 19th-century green wallpaper was made with a pigment containing a huge amount of arsenic. When the wallpaper got damp, it released toxic arsenic gas into the air, slowly poisoning and killing the home's residents.

The Killer in the Walls: Why Was a Popular Type of Green Wallpaper Once a Leading Cause of Death?

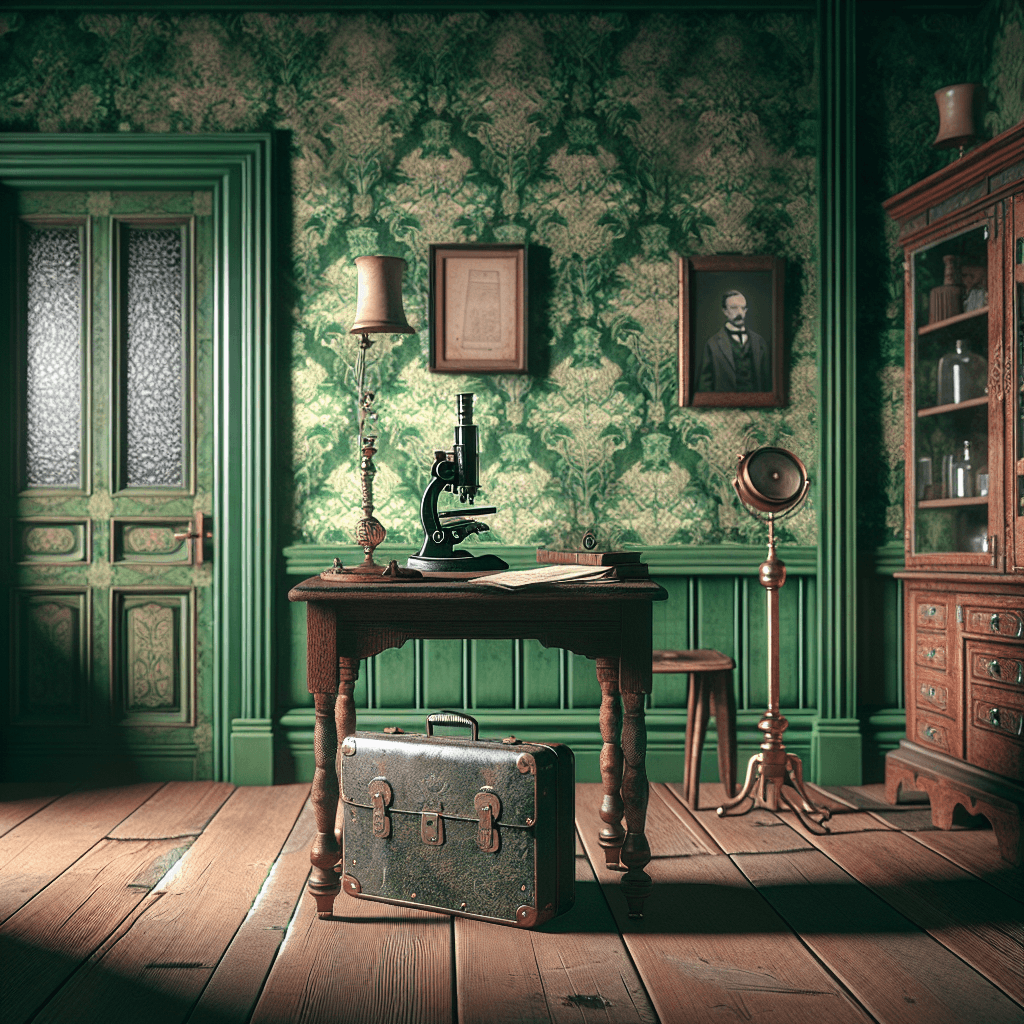

Imagine decorating your home with the latest, most fashionable wallpaper. You choose a stunning, vibrant green, a color that breathes life into your parlor and bedrooms. But soon after, a mysterious illness descends upon your family—headaches, stomach pains, and a creeping weakness that doctors can’t explain. This wasn't a work of fiction; it was a terrifying reality for many families throughout the 19th century. The beautiful green wallpaper adorning their walls was, in fact, silently poisoning them. This blog post will uncover the deadly secret behind this popular Victorian decor and explain the chemical process that turned a design choice into a death sentence.

The Allure of a New Color: Scheele's Green

Before the late 18th century, creating a bright, long-lasting green pigment was incredibly difficult and expensive. This all changed in 1775 when Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele invented a revolutionary new pigment. By mixing copper and arsenic, he created copper arsenite, a compound that produced a brilliant, vivid emerald hue. This pigment, which became known as "Scheele's Green," was a sensation.

It was not only beautiful but also cheap to mass-produce. Manufacturers quickly adopted it for a vast range of consumer goods:

- Wallpaper

- Paints

- Fabrics for clothing and furniture

- Artificial flowers

- Even children's toys and confectionary coloring

For the first time, middle-class families could afford to decorate their homes in a color once reserved for the aristocracy. Green rooms became a symbol of style and status, with wallpaper patterns by famous designers like William Morris featuring the popular shade. Unbeknownst to consumers, this trend came at a terrible cost.

A Beautiful Toxin: How the Wallpaper Poisoned People

The fatal flaw of Scheele’s Green, and a later, similar pigment called Paris Green, was its primary ingredient: arsenic. A single roll of wallpaper could contain up to 100 grams of the poison. Many people assumed the danger lay only in ingesting flakes of the paper, but the true mechanism was far more insidious and airborne.

The problem began in the damp, humid climates common in places like Britain. These conditions, combined with the organic glues used to hang wallpaper, created the perfect environment for common household molds to thrive. As fungi, such as Penicillium brevicaule, grew on the wallpaper, they would metabolize the arsenic-laced pigment. This biological process released a colorless, odorless, and highly toxic gas called trimethylarsine into the air.

Residents would unknowingly inhale this poison, especially in poorly ventilated rooms like bedrooms where they spent many hours sleeping. The result was chronic arsenic poisoning, with symptoms that were often misdiagnosed as other common ailments. Victims suffered from:

- Nausea and severe stomach cramps

- Headaches and drowsiness

- Skin lesions and sores

- Hair loss

- Irritability and confusion

- In severe cases, organ failure and death

Because the exposure was slow and steady, the connection to the beautiful green walls was often missed until it was too late.

The Slow Unraveling of a Deadly Secret

By the mid-19th century, doctors and scientists began to grow suspicious. Medical reports noted a pattern of mysterious illnesses and deaths occurring in homes decorated with green wallpaper. One of the most famous potential victims was Napoleon Bonaparte, who died in exile on the damp island of St. Helena. His home was decorated with green wallpaper, and later analysis of his hair samples showed high levels of arsenic, fueling speculation that he was a victim of his decor.

Despite mounting evidence, the public and manufacturers were slow to accept the truth. The wallpaper was simply too popular and profitable. The industry actively pushed back against the "arsenic scare," dismissing the claims as sensationalism.

The tide finally turned thanks to persistent scientific investigation and media attention. Chemists developed simple tests that could confirm the presence of arsenic in wallpaper samples. Outraged articles and chilling cartoons began appearing in publications like The Times and Punch magazine, vividly illustrating the dangers of "The Arsenic Waltz" with death. As public awareness grew, demand for arsenic-free alternatives surged, and by the end of the 19th century, the deadly green wallpaper had largely disappeared from the market.

Conclusion

The story of Scheele’s Green is a chilling historical lesson on the hidden dangers that can lurk within everyday products. The desire for a beautiful, fashionable home led to the widespread use of a pigment that silently poisoned families through a toxic gas released by common mold. This deadly episode highlights the critical importance of chemical safety and public health awareness, reminding us that the materials we bring into our homes can have profound and unexpected consequences. It stands as a stark reminder that behind beautiful facades, a scientific understanding of what we live with is not a luxury, but a necessity.