Why were houses and shops once built directly on top of bridges

It sounds like a scene from a fantasy novel, but for centuries, bridges weren't just for crossing rivers—they were prime real estate packed with bustling homes and shops. Discover the ingenious, and often desperate, reasons why people lived on these incredible structures.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: In crowded, walled cities, building on bridges created new real estate. The rent from these homes and shops paid for the bridge's construction and maintenance, while also offering a prime, secure location for business and a way to avoid city land taxes.

Living Over the Water: Why Were Houses and Shops Once Built Directly on Top of Bridges?

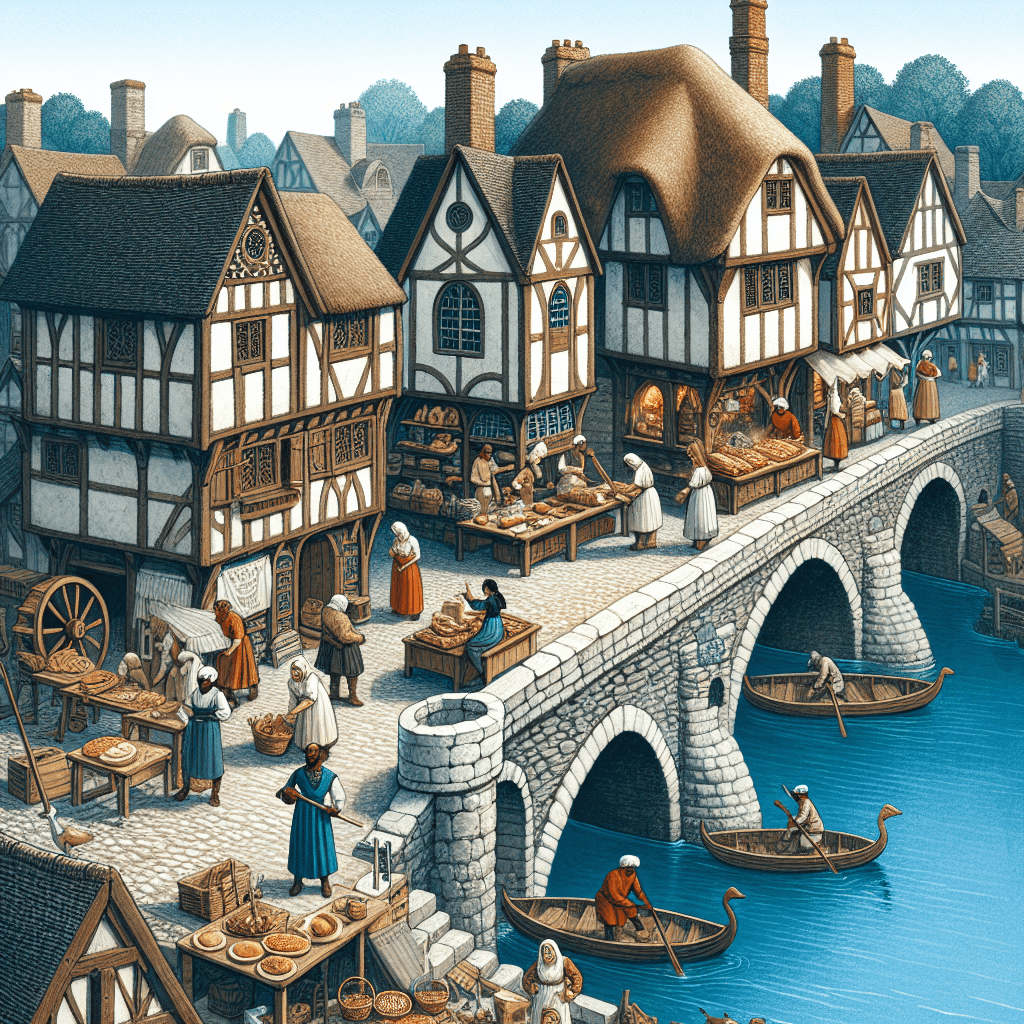

Imagine walking through a bustling medieval city. You cross a river not on an open-air crossing, but through a narrow, crowded street, flanked on both sides by goldsmiths' shops, apartments, and taverns, all perched precariously over the flowing water below. While it sounds like a scene from a fantasy novel, these inhabited bridges were a very real and often practical feature of urban life for centuries. Structures like Florence's Ponte Vecchio or the old London Bridge were not architectural quirks but ingenious solutions to the pressures of their time. This post will explore the key economic, defensive, and social reasons why people once chose to build their homes and businesses directly on top of bridges.

A Prime Location for Commerce and Trade

In an age before mass transit, location was everything. Bridges were the main arteries of a city, funneling every traveler, merchant, and farmer through a single, controllable point. Building a shop directly on this thoroughfare guaranteed an unmatched level of foot traffic and a constant stream of potential customers.

- Captive Audience: Anyone entering or leaving the city had to cross the bridge, making it the most valuable retail real estate available.

- Economic Hub: Bridges were often where tolls were collected, making them natural centers of financial activity. Merchants could sell their wares to travelers who were already stopping to pay their fees.

- Tax Advantages: In some cities, building on a bridge allowed merchants to avoid certain ground taxes levied within the city walls, making it an economically savvy move.

This concentration of commerce turned inhabited bridges into vibrant, self-contained marketplaces that drove the local economy.

Maximizing Space in Crowded Medieval Cities

Medieval cities were notoriously cramped. Surrounded by defensive walls for protection, urban centers had very little room to expand outward. As populations grew, every square foot of land became precious. Building upwards was one solution, but building on bridges was another.

This practice was a brilliant form of urban planning, creating new land out of thin air. The bridge structure itself became the foundation for new houses, shops, and workshops. For city planners, it was a way to accommodate a growing population without compromising the defensive integrity of the city walls. For residents, it offered a prestigious and central place to live and work, right in the heart of the action.

Funding, Defense, and a Sense of Community

Beyond commerce and space, inhabited bridges served crucial civic and structural functions. The buildings themselves were integral to the bridge's success and security.

A Self-Funding Infrastructure Project

Bridges were incredibly expensive to construct and maintain. The constant wear from traffic and the erosive power of the river meant they required regular, costly repairs. By leasing out the plots on the bridge to home and business owners, the city or the bridge's trust could generate a steady stream of rental income. This revenue was then used to fund the bridge's upkeep, creating a self-sustaining piece of public infrastructure—a medieval public-private partnership.

A Fortified Gateway

The buildings on a bridge also added a significant layer of defense. An inhabited bridge could function as an extended gatehouse, complete with its own gates and even a drawbridge at one end. The narrow street could be easily barricaded, and the upper floors of the buildings provided excellent vantage points for archers to defend against an attack. The famous old London Bridge, for example, had a fortified gatehouse at its southern end to help protect the city.

The Decline of the Inhabited Bridge

Despite their ingenuity, most inhabited bridges have vanished. By the 18th and 19th centuries, they began to be seen as problematic for several reasons:

- Fire Hazard: The timber-framed, tightly packed buildings were a terrifying fire risk.

- Structural Strain: The immense weight of the buildings put constant, dangerous pressure on the bridge's arches and foundations.

- Traffic Congestion: As carts and carriages grew larger and more numerous, the narrow bridge streets became major bottlenecks, strangling city traffic.

- Changing Tastes: Enlightenment-era ideals favored open, airy, and symmetrical cityscapes, and the cluttered, "chaotic" medieval bridges were viewed as relics of a bygone era.

Most were demolished and replaced with the wide, open bridges we are familiar with today.

A Window to the Past

The decision to build houses and shops on bridges was a brilliant response to the unique challenges of medieval urban life. It was a multi-faceted solution that addressed issues of commerce, housing shortages, infrastructure funding, and defense all at once. While only a few examples like Florence's Ponte Vecchio and the Krämerbrücke in Erfurt, Germany, survive today, they stand as precious monuments. They remind us of a time when a bridge was not just a way to cross a river, but a destination in itself—a living, breathing neighborhood suspended over the water.