Why were medieval people's pointy shoes legally limited by their social rank

In the Middle Ages, your shoes could be a literal crime; the law dictated the length of your pointed toes down to the inch, and wearing a style above your station threatened the very fabric of society.

Too Long; Didn't Read

TLDR: The absurdly long points on medieval shoes were a status symbol; the longer the tip, the more important the wearer. Because they were useless for manual labor, they showed off a life of leisure. Laws limited their length by social rank to visually enforce the class system and stop commoners from dressing like nobles.

The Point of Fashion: Why Were Medieval People's Pointy Shoes Legally Limited by Their Social Rank?

Imagine a fashion trend so extreme that the government has to step in and make it illegal. It sounds like a headline from a modern satire site, but in the 14th and 15th centuries, this was a reality. The offending item? A pair of shoes. Specifically, shoes with outrageously long, pointed toes known as "poulaines" or "crakows." These weren't just a quirky fashion choice; they were a powerful status symbol, and their length was so significant that it was regulated by law according to one's place in society. This post will delve into the fascinating history of these pointy shoes and explore why medieval authorities went to such lengths—pun intended—to control who could wear what, revealing how fashion was used to enforce a rigid social hierarchy.

What Were Poulaines and Why Were They So Popular?

Emerging in the late 14th century, poulaines (a name derived from Poland, their supposed origin) were soft, slipper-like shoes made of fine leather, velvet, or silk, characterized by their dramatically elongated and pointed toes. For the medieval elite, these shoes were the ultimate fashion statement.

Their popularity stemmed from what they symbolized: a life of leisure and wealth. The impractical design made it clear that the wearer did not perform manual labor. You couldn't exactly plow a field or work at a forge while trying not to trip over your own two-foot-long shoe tips. The longer the point, the more important and less mobile the wearer was presumed to be. This made the poulaine a conspicuous and undeniable marker of aristocracy, a way to visually separate the wealthy elite from the working common folk in a single glance.

Sumptuary Laws: Putting a Limit on Lavishness

As the merchant class grew wealthier, they began to adopt the fashions of the nobility, including the coveted pointy shoes. This blurring of visual class lines was deeply troubling to the established aristocracy and the Crown. Their solution was to enact "sumptuary laws"—regulations designed to curb extravagance and reinforce social hierarchies by restricting what people could wear, eat, and own based on their rank.

These laws served several key purposes:

- Maintaining Social Order: Their primary goal was to make the class structure visible and unchangeable. If a wealthy cloth merchant could dress like a duke, it undermined the God-given social order that placed royalty and nobility at the top.

- Moral and Religious Concerns: The Church often condemned extreme fashions like poulaines as evidence of sinful pride and vanity. The pointed toes were sometimes derisively called "Satan's claws," linking the trend to moral decay and impiety.

- Economic Control: In some cases, these laws were also a form of economic protectionism, aimed at preventing the expenditure of wealth on imported luxury materials used to make such extravagant items.

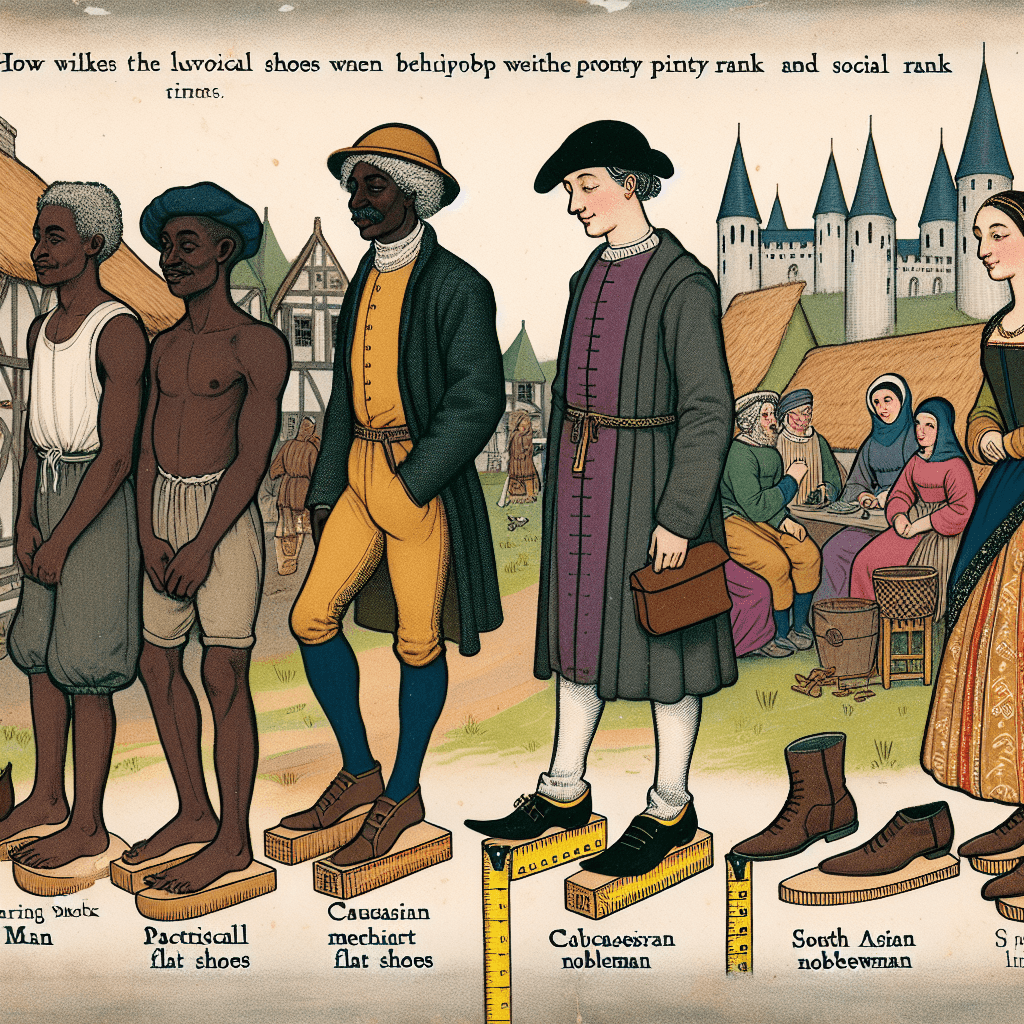

Measuring Status: The Specific Rules for Shoe Length

The sumptuary laws became remarkably specific when it came to footwear. In 1463, England's King Edward IV passed a statute that explicitly linked the length of a shoe's point to the wearer's social standing. While the exact measurements could vary slightly by region and time, the English law laid out a clear sartorial hierarchy:

- Lords, Knights, and Esquires: Permitted to wear points up to two inches long.

- Merchants and Gentlemen: Limited to a point of one inch.

- Commoners and Laborers: Forbidden from wearing any points at all.

Breaking these laws wasn't a minor infraction; it could result in significant fines. The impracticality of the longest points, worn by the highest nobility before the laws tightened, became legendary. To prevent tripping, wearers sometimes had to stuff the tips with moss or wool to keep them firm or even attach the points to their knees with small, decorative chains of silver or gold.

Conclusion

The legally enforced limits on medieval pointy shoes reveal that fashion has long been more than just a matter of personal taste. For centuries, clothing was a form of social language, strictly regulated to communicate status, wealth, and power. The poulaine wasn't just footwear; it was a walking billboard of one's place in the world. The sumptuary laws that governed them were a desperate attempt by the ruling class to preserve a rigid social order in a changing world. So, the next time you see an extravagant fashion trend, remember the pointy shoes of the Middle Ages—a potent reminder that what we wear has always been a powerful statement.